http://www.breakingnews.ie/discover/from-cork-kurt-cobain-595334.html

A pleasantly whimsical post today, a piece from an Irish website discussing Kurt Cobain’s statements about bonding with Cork.

It’s hard for any individual to feel unmoved or uninterested when their past threads are brought to light — it’s slightly more unusual in the case of Kurt Cobain. The reason I say that is simply that, outwardly at least, Kurt Cobain’s most immediate roots, his mother and father, were a cause of significant pain and dismay. For a man who deliberately seems to have avoided all contact with the latter (barring one well-known encounter in 1992) and who limited contact with the former, to feel tears at discovering the Irish roots behind his name seems over-elaborate.

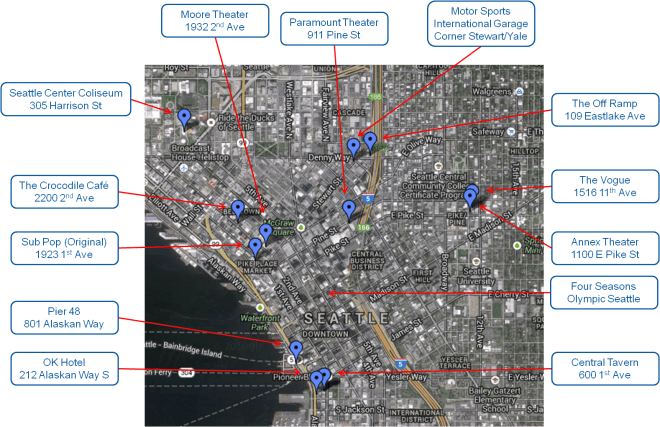

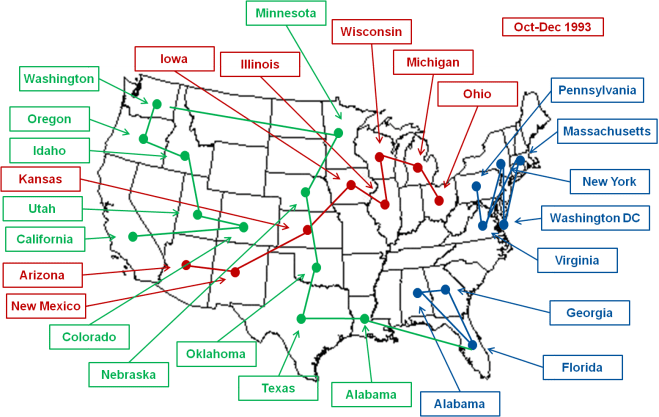

Except there he is saying it. It’s significant because, despite Nirvana’s extensive travelling, Kurt Cobain’s affections for other countries seems to have been limited — there are no tour diary tunes, the only physical locations in his songs are either fictitious or are firmly State of Washington, he seemed thoroughly unhappy in South America, has lashed the British, was barely awake or undrugged enough to notice Australasia. It’s also remarkable for the fact that his memorialisation of Seattle/Olympia/home in song wasn’t nostalgic or happy — images of poison and revenge were the primary links. But he had love for Ireland…

My take is that the answer lies in blood. Kurt Cobain’s view, expressed in his suicide note, expressed in his repeated linkage of sex, love, enslavement and family through his songs, seems to have been that genetics essentially dictated the resulting human being. The theme of biology ranks as probably the most significant core within his music and, while significantly conflicted over his parents, their importance (though malevolent) in his eyes was undeniable. Ireland was, therefore, something more than a tourist experience, more than just another gig stopover. Instead of being a journey out into the world, it was a journey into himself.

I despise it when people talk about travel broadening the mind. Most people I know come home precisely as ignorant or ignorable as they were when they went out — most come back with a pretty photo collection and some knickknacks to show for it — it’s rare that brief work breaks in a foreign culture for two-three weeks blossoms into a true insight into international togetherness or cultural difference. Travel alone doesn’t do much for the mind; it’s meaningful journeys, one’s that mean something to the person involved, that make the difference. This means setting out with a purpose, something to be reinforced, discovered, made flesh. In the case of Kurt Cobain, journeys all over the world led him no closer to comfort either with home or away.

Kurt Cobain’s words are remarkable, “I walked around in a daze…I’d never felt more spiritual in my life…I was almost in tears the whole day…Since that tour, which was about two years ago, I’ve had a sense that I was from Ireland.” He’s determined as well to emphasise the reality of what seems like hyperbole; “I have a friend who was with me who could testify to this…”

A tour guide in Egypt complained that each time a cluster of tourists joined him he was beset by “half a dozen Cleopatras and a good few pharaohs.” Essentially statements about one’s ancestors are as much a present-day gesture of identity as they are a record of truth — that’s why so many adherents of reincarnation are beset by grandiose visions of past glory (a similar phenomena is the British love of period costume dramas about the upper classes — when times are hard the British like to forget that most of their ancestors were poverty stricken miners choking on coal dust, itinerant labourers dying in their forties, or part of the many thousands of women who took to prostitution either as a trade or a temporary measure.)

In the case of Kurt Cobain, the Irish connection provides him with an alternative root — one located thousands of miles from the U.S. working class and from the alcoholism and depression that seems to have haunted the roots of Cobain’s immediate family. By looking beyond his immediate circumstance, toward a past that he could base on his sanitised modern tourist experience of Cork, he was able to remove himself from the current circumstance of his family. It’s a repeat of his desire, as a child, to imagine he was an alien baby from outer space, or images of being adopted. Visiting Cork, Ireland gave him a way of alienating himself from his real life.

It also didn’t require him to get in touch with the earthy reality of what life in Ireland, during the period his forbearers left Cork, was like. He wasn’t imagining ‘being’ his ancestors, he was imagining being himself, in the present-day, simultaneously a thousand miles from his real life and a hundred and something years after his closest Irish heritage. He didn’t have to acknowledge the squalor or misery of nineteenth century Ireland because it’s not what he was yearning for, he was just imagining being a young man who might have grown up differently. It’s the same trick pulled by those who wish to imagine a past as Cleopatra — they’re not asking to experience the dirt, dust and relative (compared to modern day) poverty of even royal life in Ancient Egypt, they’re just after a talisman of power to ward off the demons around them today. There’s a constant underestimation of how much behaviour and activity in the here and now is nothing more than a statement of “here I am and this is who I am”; the past is present as a way for people to declare their chosen alternative and mythical identities.