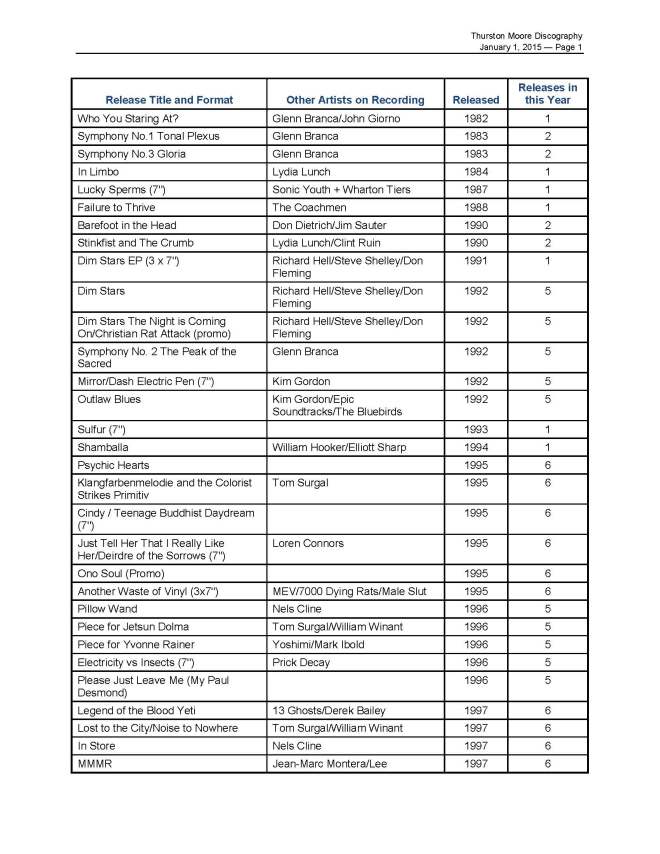

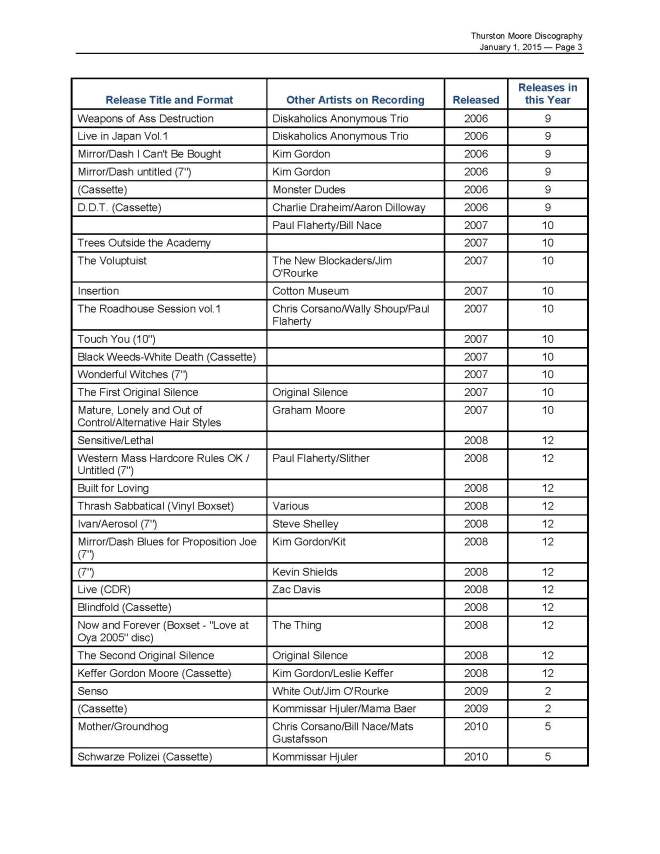

To Thurston’s credit, even with a catalogue this wide, he’s completely avoided that most ignominious musical horror; the genre exercise. There’s nothing in Thurston’s catalogue straying toward Axl Rose yelling “give it some reggae!” on the Guns n’ Roses live album and the band, oh what a surprise, being able to do a passable white boy reggae rhythm, or Snoop Dogg’s half-hearted conversion to Snoop Lion. Thurston has stepped very clearly into areas only when he has an established reason for being there. The biggest diversions are both inside the last ten years; the run of acoustic albums was well-trailed by the increasing presence of gentler rhythms and melodies on SY records – interlocked with the logical shift to semi-acoustic wintry sounding releases under his own name – making the run of solo acoustic albums perfectly comprehensible. The establishment of some kind of narrative plays an underrated role in most human endeavour, there’s a satisfaction in seeing where something has come from as well as a legitimacy and credibility derived from something that doesn’t just appear like a classroom exercise or a bored afternoon diversion. Thurston’s moonlighting with Twilight in 2014 stands as the sole example of Thurston stepping out of his ‘regular’ terrain but frankly by 2014 he’s blown so many barriers that involvement in an entity that involves a shifting cast of playing and guest stars makes total sense.

Back in 1995 though, all this was still to come. SY-esque rock was still the focus when Thurston tag-teamed a release with Loren Mazzacane Connors as part of the ‘Instress’ series on Road Cone, a Portland Oregon label. Thurston’s contribution was a track with the conversational title “Just Tell Her That I Really Like Her. The title itself is a bit of a Thurston trait actually as we’ll see with “Please Just Leave Me” and with his “Sensitive/Lethal“ release later in this piece. The track was basically a “Psychic Hearts” outtake with the unit assembled for that release presence; Tim Foljahn contributing guitar and Steve Shelley on drums – it ended up as a bonus track on the 2006 vinyl reissue of that ‘solo’ album. It sounds very much akin to that album’s results – both guitars thudding away to make up for the absence of bass or interlocking to weave pretty patterns of notes. The Loren Connors side is actually less typical of the musician in question. The echo-hazed guitar and cloudy production preferences are in place from square one but the four parts of “Deirdre of the Sorrows” feature significantly rocking qualities – the first two tracks are quite a howl before things settle into the mournful regularity of a Loren Connors tale on part three and finish with a piece somewhere between his acoustic work and his electric era – a clean guitar unpinned by a purring rhythm matching it step for step. I adore Loren Connors’ work so the prospect of more from these two together naturally intrigued me.

It wasn’t long in coming. 1997 brought “MMMR” – a collaboration consisting of Loren Mazzacane Connors, Thurston, Jean-Marc Montera and Lee Ranaldo. Jean-Marc is an intriguing fellow in his own right – founder of an experimental music organisation (GRIM – Groupe de recherche et d’improvisation musicales) in the late Seventies in the city of Marseilles. It’s worth considering the extent to which Thurston, for a time, was gathering teachers (Loren Connors born 1949, Glenn Branca born 1948, Evan Parker born 1944, Wally Shoup born 1944, Richard Hell born 1949, William Hooker born 1946) from the generation one step above his own to initiate him into the field in which he was seeking to perform. I guess a touch of hero worship can’t be ruled out either – getting on vinyl with one’s heroes and inspirations is any record-collecting fan-boy’s dream, more power to the man’s elbow! Again, it’s surprising how tight the peak of this tendency is, it stretches from “Shamballa” in 1994 with William Hooker, to the first team-up with Wally Shoup in 2000 after which it becomes hard to spot a new elder entering Thurston’s on vinyl orbit. A generational shift takes place once Thurston’s apprenticeship passes. The album itself, an all-guitar affair, is hard to disentangle, I’d be lying if I said I was clear which was Thurston’s guitar. Track two on the album brings him in to join Jean-Marc and Loren for a patient ten minutes in which humming sound-fields surge and flex beneath what sounds like Loren’s tactic of long-held notes and brief clustered phrases. Only at the halfway mark does the track begin to open beyond that ‘front / back’ formation and for the final two minutes someone other than Loren tears a far noisier hole in the piece. The twenty minute collaboration with Lee Ranaldo now involved sees each guitar chipping in phrases – brief sounds – as if finishing one another’s sentences at a press conference. It’s an effective approach of course because one can appreciate the sheer variety of what they produce. A ‘Loren toned guitar’ pings decaying notes in the blend; a scraped, crunched guitar becomes a consistent backdrop; stray notes from another as strings are mutilated and the recognisable notes vanish before they ever become something as stereotypically DONE as a riff; a final guitar shakes down electricity.

A chunk of the same sessions emerged on the Loren Connors record “A Possible Dawn” (1998) – primarily a solo release ending with a thirty minute long collaboration between Loren, Thurston and Jean-Marc. And then an exercise in patience ensued – 2011 saw the emergence of “Les Anges du Peche” consisting of the final unreleased portion of that session. The liner notes, from Philippe Robert who ran Numero Zero Audio which arranged the recording sessions, explain that the session was set up following contact during Sonic Youth’s Washing Tour when it reached France and hit Marseille. It sounds like it took a few months to arrange financing to allow recording to go ahead with the result being three days recording in New York at the Echo Canyon studios. The liner quotes Lee Ranaldo dropping in after attending “David Bowie’s fiftieth birthday party,” which Bowie staged on January 9, 1997 (the day after his birthday.) Side A of the release is one of the most rock-orientated of Thurston’s outings – essentially reads like the instrumental breaks in Eighties-era Sonic Youth, like an expanded coda to the “Washing Machine” album’s “The Diamond Sea.” Gently knocked wood plays against dreamy strums and an underlying bass throb in an extended opening gambit. The tapping swells to encompass the shiver of strings shaken to live, wayward guitar lines spiral slowly though the heart in gentle tunefulness, swiped strings creak…Then the guitars crank up a notch, all players rise to the new volume level, two guitars hold a steady backline over which the third solos until calm descends and we return to distant expanding clouds of amp rumble, sparks hitting the ground, shimmering jangled wire. There’s a heavenly unison throughout with all three guitarists matching each other’s moves to create moments, for example, where all guitars flutter on the high notes. This contributes to the effective tailing off in the outro as guitars slow, soften, fade. Of course, it does sound exactly like what I imagine Sonic Youth jammed on all the time for the preceding decade and a half but when something sounds so familiar and so good there’s no reason to dismiss it. Side B meanwhile commences with a honking, scronking set of cranked up crack and glitter from the various musicians – short sounds predominate with each musician punctuating the others’ contributions. How to describe it? One guitar might ping strings steadily, while another is strummed frantically with strings bridged or muted in some way and the third guitarist lets the amp hum or smacks or jabs at the strings. There’s not really forward motion, one combination of sound simply replaces another – one guitarist scalps his guitar, the sound of repetitive tapped bone pouring out the speaker, another seems snapped off leaving only the high notes to sound like pebbles ground together, the last echoes metallically like a struck oil drum. Again, it’s a very different approach to the majority of efforts visible at this stage – a nasty, noisy and disorganised one, but still one built round a common conceptualisation and intent that hangs it together. Toward the end something approximating the strained sound of a sampled gypsy violin comes through, awkward scrapes tailing away – it’s a sound I’ve not heard explored elsewhere on this trek through the discography and I admit I’d love to hear more of it.

2013 until the Loren Connors and Thurston would team up for another release. “The Only Way to Go is Straight Through” combines a performance on July 14, 2012 at a NYC venue called The Stone with an October 17 performance at a Brooklyn venue called Public Assembly. I’m presuming, given each side is only just over twenty minutes, that these are more like extracts from the performances but I can’t tell. There’s a sense of each letting the other lead for a performance – Side A kicks straight into what I’d describe, in a kneejerk way, as ‘Thurston territory’ with power and force to the fore, while Side B is more ethereal and feels like ‘Loren soil’.

Before deviating into the sum of Loren/Thurston collaborations I mentioned studio work, however, let me return to it. 1993 led off with Thurston’s first release of his experimental studio work on a single. It’s then a gap to 1996 when we suddenly encounter two further studio excursions (and the Nels Cline “Pillow Wand” collaboration in the background.) Thurston’s improvisational work has remained a predominantly live entity at this point even if it was increasingly being documented. A quality diversion to commence with is the “Piece for Yvonne Rainer” (initially a cassette in 1996 – I only have the 1998 CD) composed with the Boredoms’ Yoshimi and Mark Ibold from Pavement. A closer tie is that both individuals were members of Free Kitten at the time alongside Kim Gordon; it gives the impression Thurston roped them in sometime around the recording of the “Punks Suing Punks” EP that outfit released in 1996 which features a song apparently name-checking Thurston and Kim’s daughter Coco. Jesus…Frankly, your tolerance for this release will depend on how amusing you find the idea of people twanging away on Jews Harps for minutes on end. Actually, being fair, stay calm – the variety of pings and boings extracted is surprisingly high and the clarity of the recording makes it a remarkably listenable experience at high volume. Hearing Thurston, Yoshimi, Mark (and I suspect Kim’s voice at one point) chatting on in the background and either commenting on their dining arrangements or on their ability to persevere with the instrument gives this a domestic edge which appeals. Think of it as the sound of genuinely creative people who don’t just make music, don’t just make sound when the cameras are on them or there’s a few thousand quid of performance fees on offer – they’re playing or thinking about playing all the time. Hearing them actively trying to uncover new ways to extract sound from the instrument is intriguing…But, in fairness, I think it is the only record of Jews’ Harp I need in my collection. It cuts at about ten minutes in, a couple of quick shreds of random rock n’ roll then straight into the far more interesting guitar instrumental. The choice on track one is to par the guitar down to the sound of sheet metal. Raps and rumbles emanate from one guitar while another is simply left to hum. It’s a sound I’m attracted to – somewhere between dark ambience and traffic sounds building and decaying. It’s more like a collage of ideas. After six minutes or so that first idea cuts rapidly and another effort, similar in style, commences. The throb of electric from one amp is far more prominent but it’s a relaxing ebb and sway, the second guitar mimics it with a deeper tone until eventually overwhelming that early ambience. Just the addition of volume to the existing cycle adds fresh overtones and detail – the guitar starts to sound like a warning klaxon with occasional interventions by a human agent marked by sudden slaps. The track plays with electric tones for its duration. Track two dispenses with the Jews’ Harp and over the gravelly sound of an ex-Soviet conveyor belt there’s some detuned hacked chords that sound like the advance of the Terminator or some part of Coil’s unused soundtrack for the film “Hellraiser.” That breaks two minutes in to be replaced by a prepared guitar offering a sound close to some kinda Eastern chimes, quite a somnolent, plumb sound, that also falls away after a couple minutes in favour of “Confusion is Sex” era menace. By five minutes in there’s the gentlest plucking at the guitar heads – by six and a half minutes it’s shattering peals of guitar, like running a buzzsaw against metal – and then on it goes again to some fuzzed up fast chopping for ten minutes combining that absence of motion in which everything is shifting and moving so nothing is leaving the boundaries of the screen. Twenty minutes; hotel room desultory hung-over tentativeness – a neat contrast to what has come before. There’s something skeletal here, hearing the bones of Thurston’s work has he tries to find new combinations of notes and guitar neck motion.

That same year saw one piece that has always left me uncertain what to think – “Please Just Leave Me (My Paul Desmond).” The CD I possess states on the disc “You can take everything there, it’s cool, I don’t care. Yeh, I need room. I’m sick of all those fucking records man – just take ‘em. Yeh, you know, but if you can please just leave me my Paul Desmond.” (Actually it says “my my Paul Desmond” – minor quibble.) the Paul Desmond in question being a jazz saxophonist and one-time member of the Dave Brubeck Quartet. That title reference is one of the first overt jazz references in Thurston’s oeuvre and, moreover, a statement of intent requesting the removal of the music of which he’s tired, to permit him the space for something new with only this solitary jazz marker still present. It’s a single thirty-one minute long track apparently involving at least one guitar left to feedback against an amp, or on a table-top, at extreme volume then tampered with. Taps, raps, strikes to strings or guitar body, they all drag the track away from its centre which consists of the always indelibly difference whine of pure feedback. Listening to it casually, a lot of the detail passes me by. Focusing on it with greater determination it’s far easier to identify the experiment being undertaken with tactics deployed to interrupt and interfere with the nature of the roar created, to make it bend, rise, cease suddenly, resume or give way entirely to the tactile thuds and thumps against the material of the guitar. It’s an intriguing piece simply because it so clearly demonstrates some of Thurston’s actual tactics for extracting sound from an instrument. Enjoyment of this document depends on your willingness to tolerate piercing extended amplifier whine and to focus on the interventions Thurston makes throughout the duration of the recording. The glory of the record is in the gestures, both large and small, that serve to derail the combination of instrument, amp and electric – it requires a pleasure in the diversity of brief moments he can haul out from the guitar. There’s no overall flow or direction to the recording, it has a kinship to certain of John Wiese’s noise recordings which might bombard a listener with 30+ minute-long tracks each showcasing one particular effect dredged from whatever source. In this case the unifier is the desire of Thurston’s guitar to return to either zero or one – noise or silence – while Thurston tips it in various directions amid that range and ultimately changes the qualitative nature of what the guitar creates. Having achieved so much in the early stages of the session it’s a disappointment when Thurston resorts to actually plucking the guitar strings for a few minutes around the fifteen minute mark – it isn’t conventional strumming but so much had been demonstrated without any need to make that standard connection. The diversion into what sounds like a casually sampled lounge jazz piece playing on a turned down record player is a neat ending, it’s background quality emphasised by the sound of Thurston engaging someone in conversation in the background as it plays. This gentle (and rather dull) jazz does outstay its welcome – the contrast with the preceding twenty-eight minutes is pointed but, more significantly, it’s a riposte to those who would claim Thurston’s noise-making was intolerable, I’d say it’s this overlong four minutes of xylophone, polite brushed drums and unobtrusive guitar is the intolerable bit.

It’s almost unbelievable that Thurston’s dedication to collaboration and the challenges brought by cooperation/contest with others means it’s a full decade before the next fully solo full-length release. Well…OK, by full length we mean the 30 minute long “Flipped Out Bride” release of 2006 issued on Blossoming Noise. By this point in time, Thurston has become well known for his patronage and support of other artists whether through contributing songs to splits, inviting them on tour, joining in as a contributor, or simply buying tonnes of music and talking about it wherever possible. I’ve spoken before – and it’s been well-noted elsewhere – that Kurt Cobain’s main joy in fame 1991-1993 came from supporting others in the scene; well, that model was bequeathed to him by Thurston and the Sonic Youth crew who continued with it through to the present day. This release on Blossoming Noise bequeathed Thurston’s ‘alternative mainstream’ cachet to a label of significance at the noisier, industrial end of the scale – one regularly featuring artists like Aube, Merzbow, Genesis P-Orridge’s outfit Thee Majesty, KK Null, Sudden Infant, John Wiese. The noise scene was well-ensconced by that point and it’s hard to distinguish whether Thurston’s willingness to add a more high-profile recording (a studio solo release rather than just an archived live cast-off) brought more than money to one of the hubs of the scene. As for the release itself, the title track consists of an elongated rather gnarled zap of electric which throbs in various ways for a full quarter of an hour. It doesn’t outstay it’s welcome, it shares a surprising amount with “Please Just Leave Me” from ten years before in i’s fixation on what can be coaxed from the guitar when strictly limiting the degree of interference with its natural inclination – without resorting to something as ‘done’ as actually playing the thing. At twelve minutes in the raps that ping the strings against the guitar body are a direct throwback as well as being the most extensive and overt manipulation to occur. The issue is that it’s such a diversion from the initial direction, it’s as if Thurston got bored or lacked the will to continue restraining himself – that he still pulls neat stretched metal tones from the instrument is fine, but in a piece that had relied so firmly on a particular approach it’s a shame to lose the focus. By fourteen minutes the singular direction re-establishes itself at a higher tone with a undercurrent of mangling persisting behind, beneath, below to take us through to the sixteen minute cut mark. Track two, “O Sweet Lanolin”, builds a beat rapped out fairly constantly in the background while a second guitar is struck, bowed, sliced, hacked at. The rumbling beat palm-thumped into the guitar sometimes forms a breathing space before Thurston’s fresh attacks, a place of retreat but also a creeping warning – shark fin piercing the water. At four minutes in the song switches and a hum of electric intervenes before the combination of pounding and scraped interventions resumes. For all the reputation of Sonic Youth (and Thurston and Lee specifically) as the archetype string-scraping guitarists, it’s amazing in Thurston’s solo discography that it’s rare that he releases a piece in which the scrape of one object across the guitar is audible – usually it’s disguised by effects boxes and heavy distortion so hearing it relatively naked is a fresh hearing for a familiar sound. At six minutes the song becomes almost an instrumental interlude for 1983’s “Confusion is Sex” LP, a harking back to the ground out sound of that early era. Time and again this song pulls back to the beat prior to a next direction – heard as a suite of ideas built around a central theme it’s surprisingly effective and becomes easier to appreciate the movement between ideas as something more than just really dang loud whimsy. It’s also a deeply effective way to create momentum for a solo guitar track. In the absence of rhythm section or song structure a solo guitar can often become trapped – either hovering motionless or pouring out momentary inclinations to the extent that it feels similarly immobile. Here, Thurston uses the motif to mark beginnings and ends, to transition to-and-from ideas, to bind things that don’t have much more than source musician/source instrument in common to a simple structure. By the close of the track one feels one has had a Chinese banquet of small dishes wrapped into twelve minutes.

Returning to the oft-made association of Sonic Youth’s erstwhile denizens and noise, it remains noticeable how rarely Thurston crossed into the scene. The 2000s saw a significant outpouring of recordings belonging to that realm, a huge array of takes and variations owing more or less to SY’s kicked open doors while another entirely span of noise evolved out of Dylan Carlson’s Earth and more metal inclined interests. Certainly the influence of Thurston’s parent band introduced many listeners of the punk/alternative/indie field to the idea that music could be a far more factitious, fragmented and wild thing than the fairly stable forms of the (then) underground allowed. SY also patronised and promoted bands from these far out places by taking them on tour and referencing them…But Thurston’s solo work rarely coincides with such outfits. A 7” with John Wiese and a cassette performance with Aaron Dilloway – still of Wolf Eyes at that time – emerged in 2004 and 2006 respectively…That’s about it. That slim line of distinction between a noise artist and an improvising free jazz artist might seem imaginary but given Thurston’s well-testified enjoyment of many of their works it’s curious that he didn’t play more with the key figures who made up ‘noise’ as a scene rather than a sound.

Still, the depth of commitment is clear; Thurston worked with two major figures, contributed to a label then openly penned praise of the scene – on top of his interview statements. 2008’s “Sensitive/Lethal” shared not only its solo nature with “Please Just Leave Me” from 1996, but also the presence of another of Thurston’s inlay addresses to an unknown person. It’s an open hymn of praise to the then ascendant noise scene; “why don’t you come over to my house babe and help me alphabeticize my noise tapes. There’s only one we’ll really play and that’s the Haters/Merzbow banned production cassette. It is theee quintessential. And then basement jam and then wine and then marijuana and then the continuous heaven. Blessed are the noise musicians for they shall go down in history. Way, way down.” A back-handed compliment memorialising the deliberately marginal scene Thurston was a patron of – the release even came out on Carlos Giffoni’s “No Fun Productions”, one of the freshest labels in the scene. The release, however, has a difficult nature. The first track puts a noise guitar solo against a monotonous, leaden guitar rhythm. The idea in itself has an intellectual credibility, the same instrument letting lose in two completely different ways and placed alongside one another as if ignorant of the other’s existence. The challenge is that the latter rhythm annihilates any ability to observe the progression or intrigue of the noise guitar, while itself being utterly uninteresting. The constant shifting directions make it impossible to settle into any kind of mantra-like listening experience, there’s nothing meditational, but also nothing to focus on. In some ways achieving such an alienating sound is impressive but it doesn’t mean it’s an experiment that has any need to be played twice. Track 2’s crepuscular sea shanty rises and falls like an automated machine, a relentless cycle of creaks and shudders, metal on metal – listening carefully, however, there’s a second guitar playing something akin to a blue trumpet wailing in the background, the occasional throb or moan of electric. This second layer rises up over the automata, subtly layering the sound field so for a long time it goes unnoticed…And then it’s all over. Done. The final track, I’d be hard pressed to lend it a name, presses a descending high tone over the eruptions of a pummelled guitar chopping in and out…And then a simpler track arises, the bleating high pitch over a crackling, scraped and clattering guitar assault ultimately resolved as both instruments dissolve into brutal sine-tones dancing around one another, possible the nearest the release has come to a duet as well as an echo of “Pleasure Just Leave Me” and it’s similar decision to dance at those high pitches. The whole release seems to focus on this desire to use a second track over the first while maintaining minimum linkage between them – like a full album of anti-collaborations.

“Built for Loving” (2008) is primarily built on short pieces – a relatively effective way to appreciate the tones and sounds Thurston can rip out of a guitar. There’s a kinship with Lee Ranaldo’s infamous 1987 release “From Here To Infinity” LP (I once heard tell that the large etching on Side B was intended to deliberately destroy your record player needle – I don’t know the truth of that) which consisted of brief experimental noise loops. There’s that feeling that this is a simply excerpts from a much larger library of tests Thurston has built up over the years – no proof but it would seem odd if these pieces were recorded solely for this release. There’s a compilation feel to the blend of brief song fragments that seem to be sketches for a late-era (re: mellowed out) SY album, the basement tape hardcore group effort at one point, then the different versions of torn out noise. The porn film interludes don’t really lend much to proceedings – they’re neither integrated sufficiently to provide a backdrop to anything music, nor warped or deranged enough to be intriguing in and of themselves. The brevity of the pieces is to their benefit and that isn’t a criticism. While live improvisation with a collaborator permits someone else to lead, to make decisions, while one rests and gathers one’s own muse, a solo setting puts a lot of weight on a single individual which has a consequence with individuals either tempted to over-perform (too much happening) or to coast (too little.) A brief solo piece allows a set arc or destination, allows a sound to be explored, shuffled, prodded and then halted as it reaches its end. Here, in vinyl format, it’s possible to hear even the longest tracks as discreet events, as suites. The release certainly highlights the difference between Thurston ‘playing’ versus Thurston quite clearly evading any such action. Side B’s final five minute piece, “Sex Addict”, are the most satisfying with the use of silence and space surrounding each emerging sound – whether submarine sonar pips, or the dry stutter that runs through most of the track, it’s an idea taken for a ride. Similarly, side A’s conclusion, “Los Angeles”, inhabit a particular type of noise for a period of time then depart. What’s the difference between purposeful noise and noise? I think it’s a sense of remaining with a recognisable sound without twisting it so far it becomes something different, yet continuing to see how that one sound can be tweaked and driven within its boundaries…And knowing when there’s nothing more to dredge from it. Side A track “Hell” heads too much that way for me; the sound has reached its limit within the first thirty seconds, it’s essentially a beat made on a vocoder – it does one thing, nothing more, all you can do is move it faster, slower like a microwave tone telling you it’s done. I guess it’s also fair to mention that the release sits alongside a long-running porn-thread in Thurston’s work starting with the angelic visage of Traci Lords on the 1990 12” “Disappearer” single, continuing with the “Weapons of Ass Destruction” collaboration and onto this one release. Then again, it’s not unique to SY – the band’s interest in America’s trash culture is well-documented, Madonna’s entire shtick continues to the present day in the pop world – it’s all representative of America’s yin-yang relation to commercial sexuality and the female body in general but let’s not go into that here.

A crucial concluding point here is how rare these true solo efforts are and that there’s a clear trajectory within them. Thurston’s discography, runs to some 127 releases yet ultimately the only completely solo releases of the Nineties are the “Sulphur” 7” in 1993 then “Please Just Leave Me” in 1996 with the partial diversion of “Piece for Yvonne Rainer.” After that there’s a silence for some ten years – Thurston devotes himself to a ten year spell in which his discography only features collaborative works. It emphasises the sense of a musician both seeking to learn from others and also enjoying the musical pleasure of communion and community. The paucity of solo work makes it easy to suggest that 2006 onward is a significant divergence. There are actually three strands at that point. Firstly there’s the continuation of his electric guitar work via “Flipped Out Bride” (2006), “Sensitive/Lethal” (2008) and “Built for Loving” (2008.) Secondly, he deviates significantly in terms of his regular instrumentation into a number of solo acoustic explorations consisting of “Suicide Notes for Acoustic Guitar” (2010), “Solo Acoustic Volume 5” (2011) and “12 String Meditations for Jack Rose” (2011) – prior to that the most visible acoustic pieces involving Thurston had been 1994’s “Winner’s Blues” kicking off SY’s “Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star” then a piece called “Altar Boy, Church Basement” on the “Hurricane Floyd” release of 2000. The use of an acoustic in a guitarist’s vocabulary would barely raise mention except Thurston’s reputation and discography is built so solidly on electrics that the sudden emergence in just those two years makes as big a point as SY’s attempt to shake off the mainstream/alternative/grunge hangover in 1993-1994 does; it’s a deliberate wrong-footing of audience expectations and a documenting of an aspect of his work that’s either been unseen or has taken this long to gain confidence or is simply ringing the changes while coinciding with his more mellow approach around this time. There’s also a far smaller thread of solo releases that pointedly emerged on cassette; “Free/Love” (2006), “Black Weeds-White Death” (2007), “Blindfold” (2008), then a true oddity, the “Voice Studies: Love Song as a Lion/Lonely Charm” cassette of 2011. Thurston acted as editor for the book “Mix Tape: the Art of Cassette Culture” published in 2005 which posited the cassette mixtape (and the more current cassette underground) as a form of folk art and lo-fi communicator among scenes and musicians without the money to press vinyl or CD – it seems no coincidence that he should suddenly add his weight to the cassette scene just as even cassettes gave way to downloads as the cheapest medium for new bands to share. Thus, the break back to solo improvisation combined with two further breaks in Thurston’s output – one instrumental, the other related to the medium used.

For me, these truly solo releases allow an opportunity to study Thurston’s technique in isolation, without distraction. It’s his omnivorousness as a guitarist that has always made him hard to peg to a specific sound while clearly marking his work. While not underrating the deeper complexities of their abilities, someone like Derek Bailey, or Loren Connors, has a signature based on the guitar deployed with a particular instrumental technique. Thurston roots his style in the use of the guitar as a channel, not for the motion of his hands, but for the sounds that can be created from it – this includes incorporating and manipulating sound produced by the amplifier (and by amplification) into a complete loop dissolving the boundaries between player-instrument-equipment. At times he’s merely tempering or unleashing the sounds a chosen combination of amp and effect is producing – a gateway, a limiter, an accelerant. That’s the key aspect of the ‘Thurston Moore guitar sound’; he doesn’t slave the guitar to a technical expression of fast finger-work, nor to a vast interest in the playing of traditional chords and notes. That isn’t to say he isn’t in control but his confidence is clear in how he’ll acquiesce to a momentary impulse – tapping, muting, plucking, strumming, rapping, punching – and see how the instrument reacts. He then decides whether the result is something that should be cut off at once, or permitted to proceed, or repeated for further study and investigation. At times he’s effectively ‘unplaying’, evading anything as practised as soloing or as posed as rhythm. Thurston Moore, in his more out-there ventures, is willing to surrender to the instrument; a unique and very intriguing characteristic of his playing. The flipside to that is his usually quite choppy and savage mastery when he does choose to play nice – even on acoustic he hacks out chords and very audibly strikes the guitar strings in what a more mannered guitarist would think of as an uncultured style. He evades traditional technique through constancy, his core tactic is to have one hand strumming without any allegiance to a traditional time signature with deviations created via a shift in position or combination on the guitar neck or a change in tempo. The result is a more liquid progression rather than the ‘blocks’ from which most guitar music is formed. It’s like continuous soloing and it’s what marries Thurston’s improvisational approach to his alternative rock chops.