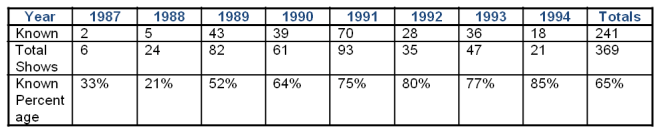

With only three sets of comparable data trying to state a definitive and rigid prediction is simply impossible. What yesterday’s post and today’s post are presenting aren’t in anyway scientific measures — it’s just as easy to say Nirvana had releases in 1989, 1991 and 1993 so they’d obviously pump an album out for late 1995. Reemphasizing the difficulty in such a clumsy rule as the gap between first and last song played live from an album, if Talk to Me was to feature on a mythical fourth Nirvana album then taking its Nov 1991 appearance as the start date, Nirvana were overdue for an album as early as July 1994 — that’s the problem with limited data…

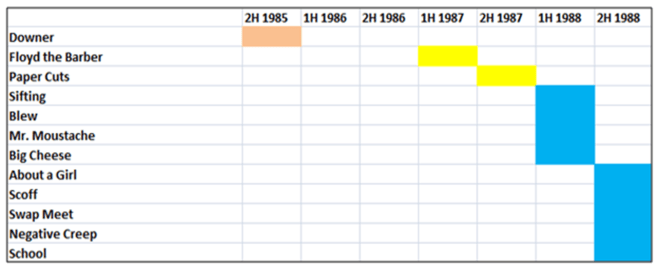

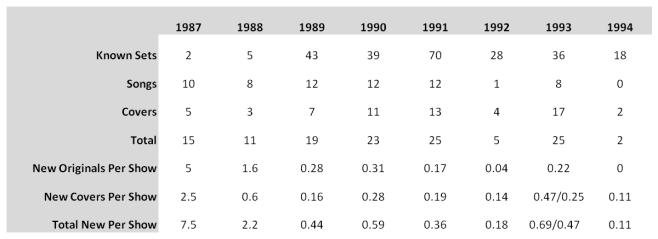

Let’s try it another way. In Dark Slivers I tried to pin down Kurt Cobain’s writing to likely periods of six months, it’s impossible to go further and naturally a few songs will shift period if new information appears. This meant working from known demos, live dates, likely evidence (i.e., the news story Polly was based on.) While not as precise as the live appearance data it’s still possible to attempt to measure the first and last songs being developed prior to an album to show how a Nirvana album evolved over time. Let’s start with Bleach:

Gillian G. Gaar argues convincingly for Fecal Matter having been recorded around March 1986 but still it’s unclear if Downer’s origins were in late 1985 or early 1986. I’m also shy of placing Downer here simply because it wasn’t Kurt Cobain’s choice to include it on Bleach, it was Sub Pop’s. Now Nevermind:

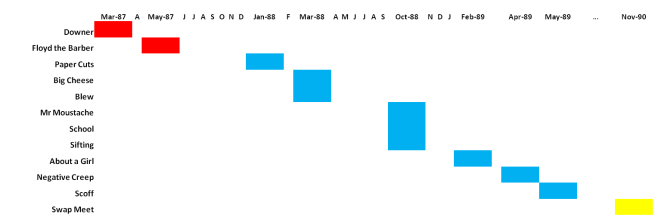

Some of the first half 1991 songs may have already been sketched out in 1990, hard to say but the overall pattern is still clear. Again, note the one ‘early riser’ then the clicking into place over the two years prior to an album. Finally, In Utero:

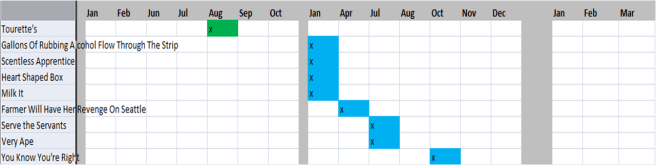

A far more ramshackle pattern and with a few provisos. Firstly, Krist Novoselic believes Tourette’s was first written in late 1989, but the earliest evidence for it is a ten second run-through of the main riff during soundcheck in November 1991 so either it stays where it is or it fills that gap between Rape Me and Heart Shaped Box. The consequence would be to shorten the album’s development down to three years.

As it stands, and compared to yesterday’s fairly sturdy pattern in the live performances, what we’re looking at is a greater span of potential. Eliminating Downer brings the development of Bleach down to a mere two years. Shifting Tourette’s into the 1991 slot makes In Utero a three year process. Nevermind, however, remains a four year project. Returning to the attempt to estimate when a fourth Nirvana studio album may have arrived, let’s take You Know You’re Right’s appearance in October 1993 as the de-facto starting point, seeing as we have so little else to work from. We’re hitting second half of 1995 all the way to first half of 1997 to finish writing meaning an album release anywhere between first half of 1996 to the last half of 1997.

There’s nothing unexpected here in predicting a wider gap between In Utero and the next Nirvana album. To get In Utero out just two years after Nevermind Kurt (and the record label) had needed a further year and a half, even leaning on the half-a-dozen songs already in place. By comparison, to create Nevermind, Nirvana had started from scratch with just one song dating before late 1989 and it had taken a full two years to get the rest done. Following In Utero we’re looking at a situation comparable to the latter example; there was next to nothing in the vault the band could kick off from, they were starting from scratch.

The only hope would have been scraping together Opinion, Talk to Me, Verse Chorus Verse, together with You Know You’re Right and Do Re Mi to make a bedrock of five songs up to first half 1994. Even then, however, staying true to form, Kurt Cobain would likely have needed a crucial year and a half to wring another seven songs out. He admitted himself he was never a prolific writer, he was neither a miracle worker, nor blessed with the equally divine ability to pull songs out of his ass — he would have needed free time and inspiration to get more out.

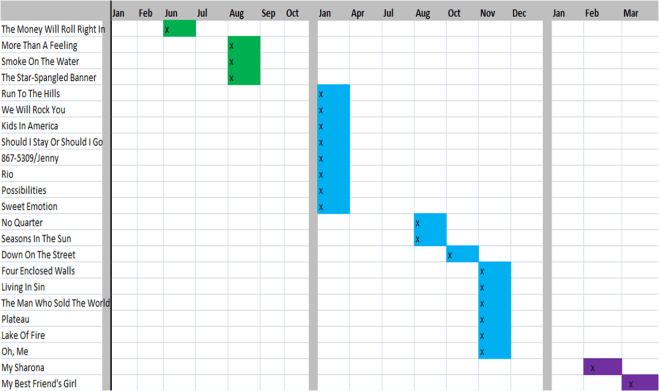

In conclusion, if we extrapolate from the gap between first and last song for an album to appear live, we’re talking an album sometime December 1995 to July 1996. If we look at the overall developmental path for Nirvana albums, the earliest date is still on track, first half 1996, but the potential late date is pushed out as far as second half 1997…

…But then again, it’s art, not science. Nirvana may have bucked the trends of their album development, and the trends of 1993-1994 in general. Rebirth and rejuvenation were possible. But there are quite a few ‘ifs’ involved. Either way, a longer wait was likely.