There were clear gaps in the live record, songs that showed up far later than seems realistic or that simply don’t show up at all. This post is just a brief look at those two circumstances.

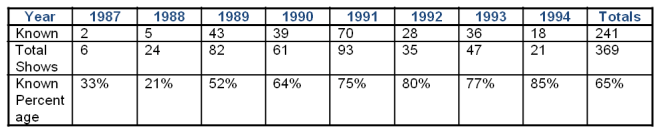

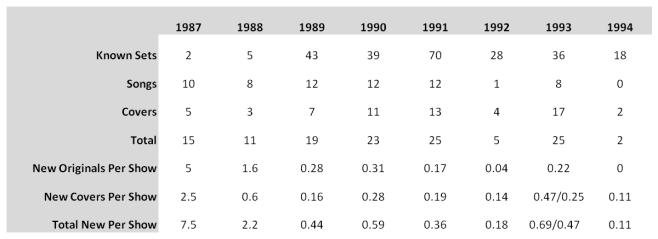

The early days of the band were deservedly the core of Gillian G. Gaar’s latest book Entertain Us. Beyond the reprised tale of rags to riches, the early days retain a mystery. The band’s rising status and ‘most likely crossover success’ status in 1990 owed a lot to Sub Pop’s success at shoving a low-selling strictly local scene onto a global stage — in 1987-1988 this was just one band in a field of thousands. The live stats support this with just 7 of 30 set-lists known:

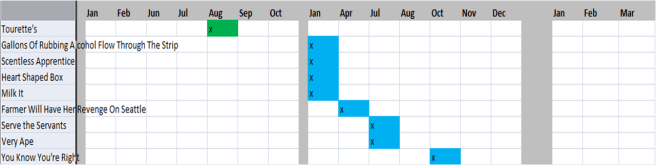

Understandably this leads to a raft of suggestive stats. As a first example, the fact that Annorexorcist appears in the set-list in mid-1987 and then again six months later in January 1988 suggests it likely featured at two further intervening shows. Likewise, given it was a leftover from Fecal Matter, there’s a possibility it may have appeared at the two shows prior to its May 1987 appearances. Raunchola (A.K.A. Erectum) flops into the territory of God knows — a first appearance in January 1988, a last appearance in March with just one intermediate show, yet then a space of sixteen performances until the next fully revealed set. There’s simply no way of knowing when either song died out. There is, however, good reason to believe there was more live life to them than there strictly limited edition status. Pen Cap Chew and If You Must also have a chequered history; they appear at the start of 1987, are excluded from the May gig (though Pen Cap Chew did make the KAOS Radio performance), then reappear in January-March 1988. In conversation with Jack Endino early in 2012 he stated, with regard to If You Must “…at the time we recorded it (Jan 88), they were opening their set with it. Much later he decided he didn’t like it, who knows why.” There’s a good chance that he’s correct and that both songs featured in the final two gigs of 1987 but then hard to discern if the January 23, 1988 appearance was their final showing or if they made some brief resurrection later in the year.

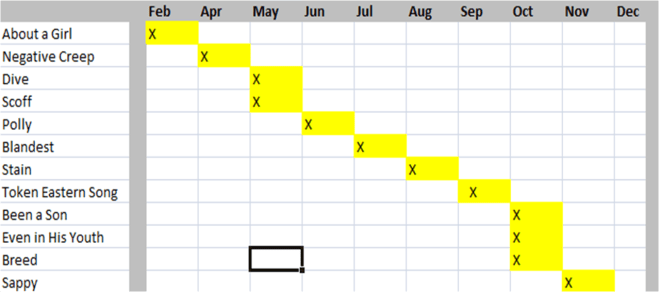

We’re looking at the gap between reality and posthumous truth. Vendetagainst (A.K.A. Help Me, I’m Hungry) exists for a brief appearance in 1987…Then a gap of 83 shows and 29 months until it pops up twice; November 5 and 8 with a gap of one show. Blandest, only ever seen on June 11, 1988 in studio, likewise appears for two shows in July. Blandest may have been present at the eight ‘ghost’ shows between March and that date, or the show a week later in Ellensburg. It’s also hard to believe that the song wasn’t featured at all earlier.

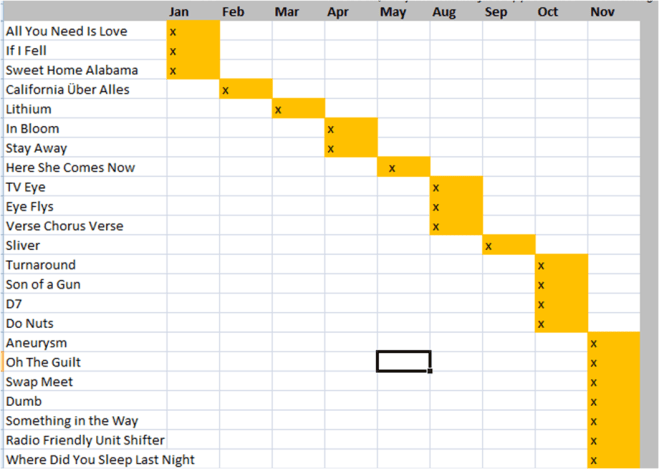

On a related note, it isn’t a surprise Chad Channing knowing Blandest, but it’s unusual that he would be aware of Vendetagainst, a song recorded a full year before his arrival in the band. I’m speculating but, in the month pause between their show in August 1989 and the commencement of touring in late September, the band seems to have decided to take stock of the songs they had left in reserve and trained up on them. During this phase the band are varying elements of their set almost nightly, it’s as if they’re keeping material alive with new releases in mind. The set is knee-deep in, as yet, unreleased songs; Token Eastern Song, Dive, Polly, Even in His Youth, Breed, Vendetagainst, Sappy, even a jam on Hairspray Queen. Nirvana were a very smart unit, already one eye to the future and a range of possibilities.

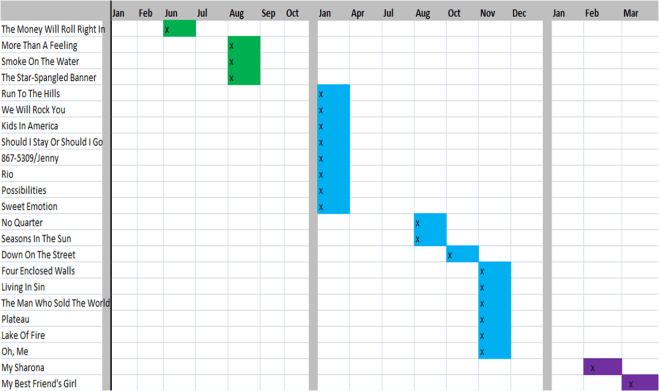

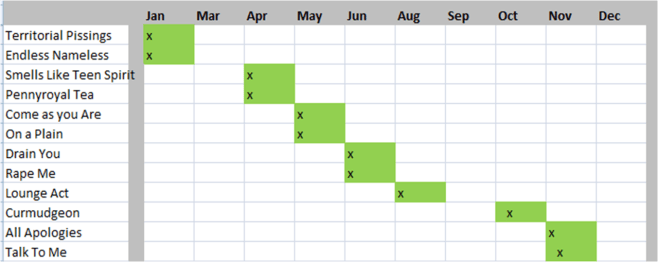

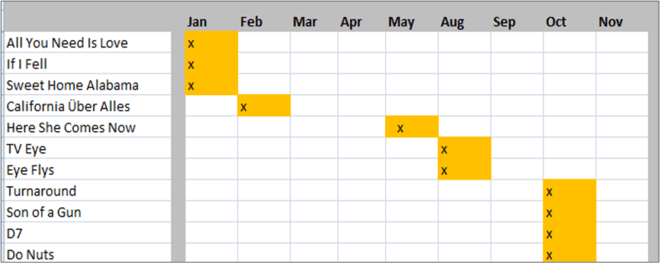

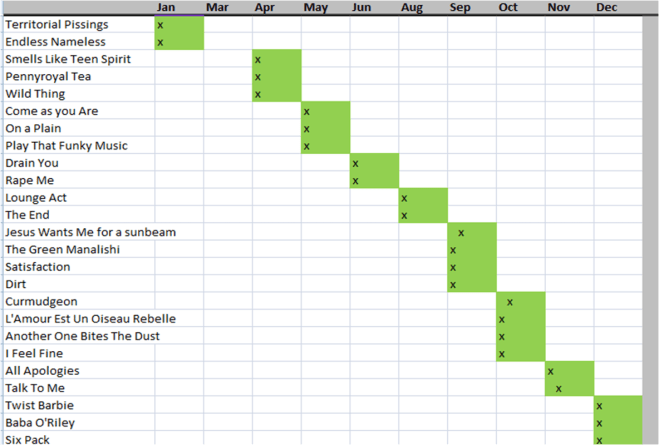

While unsurprising that the rarities are conspicuous by their relative absence from the live record, it’s fun to consider the fate of a certain portion of Bleach. Essentially the gaps in the known set-lists cast a veil over the likely presence of some songs. Blew, Mr. Moustache and Sifting were all given a first airing in June 1988 in studio, but eight set-lists are unknown meaning it’s October 30, 1988 before the songs are first seen. Likewise, it’s unlikely that Negative Creep and Scoff were first performed when they’re first ‘visible’ to us twenty years later, in April and May 1989 respectively given they were definitely finalised and recorded by the start of the year and there are ten shows leading up to the known displays.

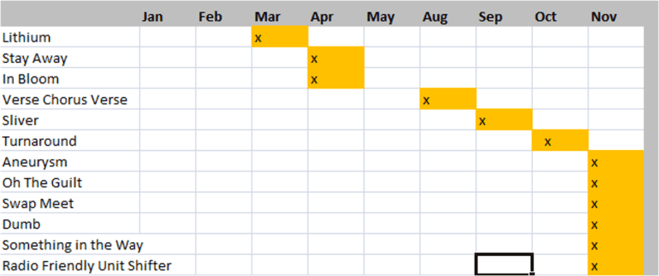

The most remarkable disappearances from the Bleach sessions are Big Long Now (I dissect it’s likely performance in the Songs The Lord Taught Us chapter of the Dark Slivers book) and the way Swap Meet doesn’t appear at all until November 1990 — that gap for the latter just doesn’t ring true. A further curious feature is that, with the exception of Blew, the ‘late arrivals’ from Bleach into the Nirvana live record are all clustered toward the back-end of the album. Apparently Bruce Pavitt and Jonathan Poneman were involved in deciding how to sequence Bleach and it’s quite intriguing that those songs that were rushed into place to fill out the album, that weren’t ready for live performance until late 1988 or even later in 1989, were all shoved to the rear. The first side of Bleach places some of the band’s earlier recorded works (Floyd the Barber, Love Buzz, Paper Cuts) to the front of the album so it seems Sub Pop were aware at the time that certain songs were rush-jobs.