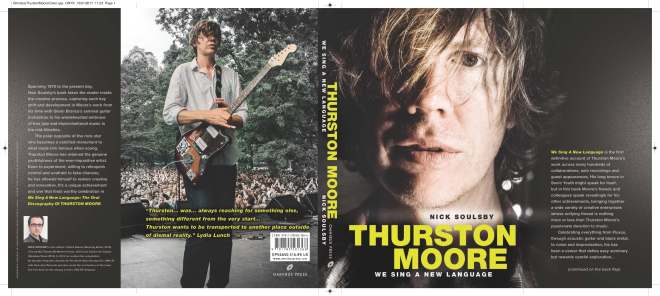

An oral history of the ’70s downtown NYC scene that made Thurston Moore

An edit of the early portion of the “We Sing A New Language” book surveys the spell where Thurston Moore was embracing the opportunities to play in NYC and was invited to become a member of The Coachmen: their ‘official teenager’ as JD King, the band’s founder, calls him.

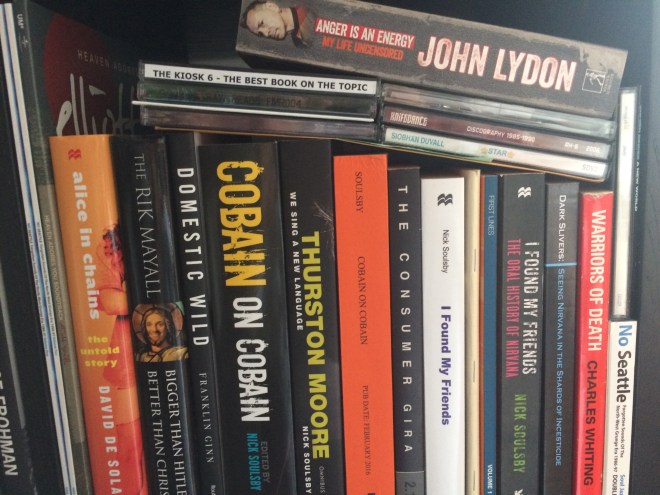

Biographies focused on Sonic Youth (an amazing band and worthy subject of study) underplay the extent to which Moore used his early years in the city, extending on into the first couple years of Sonic Youth, to experiment, learn, take part in whatever was going on at the time. He played in The Coachmen (art rock); Even Worse (art punk); in a variety of one-off combinations with artists like Stanton Miranda, Ann Demaranis, Elodie Lauten; as stand-in bassist for SWANS; as part of Lydia Lunch’s In Limbo band; as part of Glenn Branca’s symphonies and touring band; as part of Rhys Chatham’s Guitar Trio outings. It’s a fertile and intriguingly varied period of time that I couldn’t help but spend a lot of time focused on: life is fascinating when it hasn’t yet assumed a single shape.

…But that’s what’s most fascinating about Moore’s trajectory: the multifaceted and expansive nature of those early years, the embrace of music as a social experience and a creative pleasure, has never ceased. That’s why I’ve found myself such an avid follower of his works and why I actively wanted to spend nights and weekends for a year-and-a-half hearing people talk of their part in it. It wasn’t about ignoring Sonic Youth for aesthetic reasons: it was about providing an extended vision of Moore as a complete artist, assuming the reader knew Sonic Youth, then giving them a window into this wider world they might only have seen slim parts of.

The stereotypes are “oh he only plays noise”, or that it’s all improvisational: that’s a deeply reductionist vision of what emerges. In the early years (1978-1984) he’s mainly a part of other people’s musical visions, lending his own talents to what they want to hear, sometimes unrecognisable as the guitar player he would become. The mid-eighties are dominated by busy years for Sonic Youth leading up to Daydream Nation around which time, the four members having firmly established themselves as artists, each feels ever more able to step beyond the band, play in other contexts, bring ideas back to the fold.

The alternative explosion sees another curious spell in which Moore (and the other members of Sonic Youth) spend extraordinary energy on cover songs and tributes and drawing attention to the music of the underground that the mainstream utterly ignored: a lot of the world acted like ‘an alternative’ only came into existence with Nirvana’s Nevermind. The focus on U.S. hardcore is visible both in the solo discography and in Sonic Youth’s output around ’92-’93.

The improvisational urge, the fascination with free jazz had been percolating for years and – after Barefoot In The Head in 1988 – there’s an explosion from the mid-nineties. There’s a decisive moment where it would have possible to just go on chasing the mainstream zeitgeist; celebrity guests; MTV appearances…And instead the mature artist dives back into learning how to play in new ways and new forms.

Moore’s work trails vines all over the most exciting new sounds of the era. He’s engaging with remix culture in a full-on way few rock artists were quite ready for; he’s working within the illbient scene quite readily; the internet’s potential is embraced with DATs and files flying across the world; he’s playing in the Nemocore ‘scene’ in which the rules are no acoustic instruments, no drums or simulations of drums; his celebrity leads him to working on soundtrack material (and ends up with the resurrection of The Stooges amazingly enough); he’s working with visual artists and in gallery spaces at a time when that kind of cross-channel approach wasn’t yet an established norm in the art world let alone among musicians. The nineties may be when it became most difficult to keep up with Moore’s release schedule but it was one hell of a fertile growth for a guy formerly known only for working with the medium of rock.

The 2000s are when, increasingly, Moore works with artists who can – in some ways – be considered children of the scenes he’d been a part of in the eighties. The noise scene, the free folk/freak folk/whatever movement, the continuation of experimenting with the potential of the guitar as a solo sound source or as a component within other terrain – it’s all there. And, in an era where ever more talk was focused on the irrelevance of the physical and/or ‘place’ in music (nonsense by the way!) Moore (and Byron Coley, Chris Corsano and a variety of comrades) forge a music scene of their own in Western Massachusetts playing at local art spaces, creating venues (Yod), setting up record labels and record shops, staging mini-festivals and art happenings, inviting touring bands, funding releases by other musicians…

And what of now? Moore in the 2010s could be forgiven for slowing down or for it being a decade of ‘more of the same’. Instead it’s been a case of adding more to an already wide-ranging muse. The importance of Moore’s poetic works, writings and performance thereof cannot be understated: it’s been a significant part of his output both in the form of limited edition volumes, his time teaching at Naropa School of Disembodied Poetics, numerous live performances, musical backing for poets like Anne Waldman or Steve Dalachinsky, pieces published in magazines like Sensitive Skin magazine (https://sensitiveskinmagazine.com/rabo-de-peixe-thurston-moore/), numerous appearances documented on Fast Speaking Music (https://fastspeakingmusic.bandcamp.com/). Similarly, his long-held support of black metal led to the Twilight album (a new highlight), to a spoken word appearance with Krieg, to the Offerings 12″ of 2016 – long may it continue: the textural assault and twisted approach to rhythm and style embodied in black metal is a perfect new home for Moore.

There’s so much going on out there, never forgetting his continued enjoyment of playing in a full on rock band mode: Rock N Roll Consciousness (capital N tribute to Lou Reed’s Rock N Roll Animal), as a title, for me, evokes Moore’s nature: rock n roll was meant to be about rebellion, youth, making something anew – that relies on people who want it to go on growing, mutating, providing a home for the creative freaks and the charming madmen. Moore may have set his sights far beyond the confines of rock music but, in doing so, I can’t think of anything more rock n’ roll in its defiance of expectation.