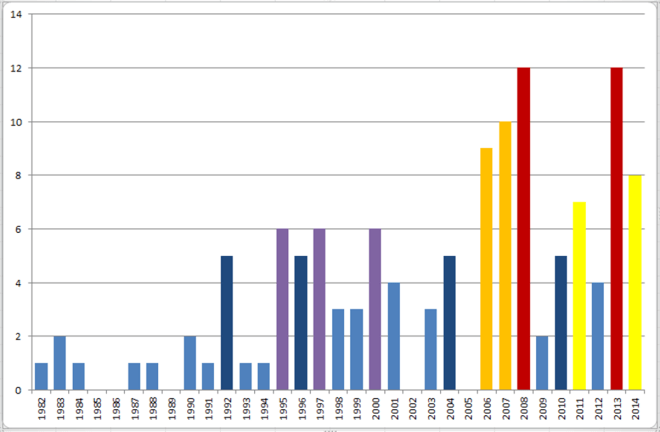

As I mentioned, as the discography explodes it becomes harder to focus on the change that’s occurring within it – my rambling today is specifically about trying to pin down what Thurston’s journey has been after 1995.

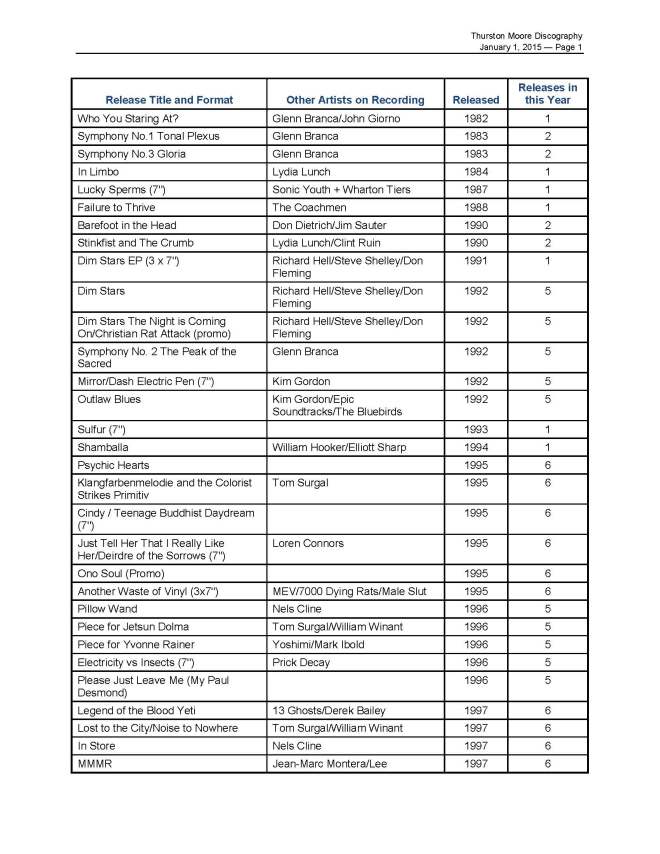

To commence the exploration, as discussed, Thurston is primarily a collaborator, an individual who thrives on working with or as a foil to another. Initially, across the Eighties, those opportunities are confined by being part of an underground band needing to work day jobs right through until the release of “Daydream Nation” and therefore limited in terms of where and when they can work with others. The collaborations are, therefore, solidly rooted in New York City. No points for stating that those initial colleagues are parent to SY’s style, Glenn Branca, then Lydia Lunch who acts as the binding figure between the gothic end of the underground in the mid-Eighties back to late Seventies No Wave. Borbetomagus and Wharton Tiers are part of the cluster within that one city. The geographic boundary doesn’t change much across the early-to-mid Nineties – Richard Hell and William Parker are both New York-centred musicians. What follows is that as 22 solo releases in the thirteen years from 1982 to end of 1995 becomes 23 solo releases in the five years from 1996 to end of 2000, the range of collaboration expands hugely.

There’s still a core during this spell. Loren Connors, Don Fleming, Christian Marclay and Tom Surgal – they’re all consistent performers within the New York artistic community. The latter is also Thurston’s most consistent collaborator in this late-Nineties phase, performing on four releases between 1995 and 1998 with a further collaboration in 2000 plus a performance with Surgal’s unit White Out released in 2009. This reinforces the sense of a musician in transition, exploring a new scene in familiar and known local company with forays out into the beyond. There’s also a physical logic to it – it costs money to tour, it costs money to travel and therefore multiple collaborations across a lengthy time period are more likely if musicians live in close proximity, a fair rule of thumb. There are two shifts, however. Firstly, the geography of collaboration expands to encompass the U.S. with musicians such as William Winant (California), Phil X. Milstein (Boston), Wally Shoup (Seattle), Nels Cline (California.) From the inauguration of Thurston’s ‘out’ phase on 1994’s “Shamballa” to the end of 2000, of 24 groups/individuals on releases with Thurston, 8 are NYC-based, 7 from further afield within the U.S. What’s potentially more surprising is the burgeoning work with artists from further afield; sure Yoshimi of the Boredoms is playing in Kim Gordon’s Free Kitten at the time but then there’s the addition of William Parker, Derek Bailey andAlex Ward’s XIII Ghosts plus Dylan Nyoukis’ Prick Decay all from Britain, then Italy’s (Cristiano) Deison, Walter Prati and Marco Fusinato, plus France’s Jean-Marc Montera and finally a very significant figure in Mats Gustafsson of Sweden.

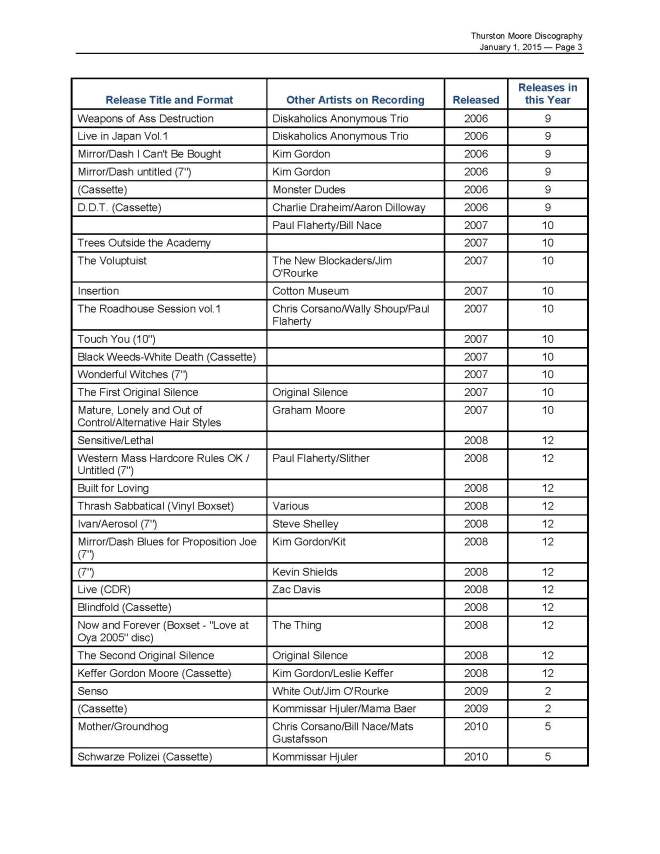

After the year 2000 this globe-trotting aesthetic takes over completely with the New York root now something revisited but no longer solidly attached. The lengthy relationship between Gustafsson and Moore has been the most solid of the past decade and a half encompassing some eleven releases in various guides (named, Weapons of Ass Destruction, The Thing, Original Silence) but we’ll come to that. Surrounding that core has been a fairly even split between new U.S. comrades such as the Paul Flaherty and Chris Corsano duo, Bill Nace, John Moloney; old comrades such as various Sonic Youth members, Beck Hansen, Loren Connors; then one-off release with non-U.S. residents such as My Cat is an Alien (Italy), Gabriel Ferrandini, Pedro Sousa and Margarida Garcia, the New Blockaders…

The scale of unit in which Thurston works remains a curiosity to me. In his best-known ‘day job’, he was part of a four-piece and he starts off in massed guitar ranks under Branca. Yet his collaborative explorations outside of SY tend to remain focused on duos and trios – even a four piece isn’t that common though there’s a big exception in the form of the Original Silence tour where the Weapons of Ass Destruction trio paired up with Terrie Ex (ex of The Ex a glorious Dutch outfit), Massimo Pupillo (ex of Italian experimental group Zu) and Paal Nilssen-Love (a Norwegian-born performer.) As a live experience it was awesome, on disc it’s kinda cluttered – but then I don’t like much orchestral classical music either so I’m not best placed to comment. One consideration behind this fidelity to smaller units is simply cost. The big band era of jazz ended primarily because the money required to transport, set up and adequately compensate musicians was too great to make touring economical. It wasn’t possible to flex ticket prices sufficiently in relation to the scale of the musical unit performing therefore large ensembles tended to need alternative sources of funding other than ticket-buying audiences. The same went for recorded performances; a label wanted to play flat fees and percentages not wages or salaries per individual – the result? Smaller units become fashionable because they make economic sense with that imposed model. The ultimate end result is the solo artist who can buy the music in on a one-off basis via producers or session musicians – it isn’t just flexibility, it’s cost-effective too, hence why hip hop is the music of modern neocapitalism far more than the Rolling Stones ever was. As Thurston emerges from the rock idiom it’s not unreasonable that he’s used to the norm of three or four piece bands – despite the occasional number-busting no wave exercise like Mars’ “Don Gavanti” opera (check it on the Atavistic label if you ever get a chance.) Entering cash-strapped avant-garde jazz also serves to keep the units small-scale. Would it be interesting to hear Thurston test his mettle against vast orchestras of individuals? Maybe. Either way, in terms of his activities so far, Thurston has primarily been a man who’s collaborative works are with units of traditional rock band size – not unusual.

(Thurston Moore and Andy Moor – May 2013)

So, having tackled the sideshow of geographical reach and the non-show of unit scale, where next? The primary shift differentiating Thurston’s work in the rock-focused era prior to 1995 versus the succeeding twenty years (now over half Thurston’s time in music) is the shift in instrumental accompaniment. Only a limited amount of the work post-1995 involved fellow guitarists as the primary partner. The main continuation was the drummer. Thurston has worked with a succession of individuals in that role across the discography – Steve Shelley, William Winant, William Hooker, Tom Surgal, Toshi Makihara, Chris Corsano – and drums remain the most common accompaniment to Thurston’s solo work, it was even the predominant partner as Thurston found his feet as a live improviser. Very clearly, however, this is rarely the 4/4 beat approach at work. Thurston thoroughly escaped the tyranny of the beat (a phrase I stole from a Mute label compilation about a decade ago and that has always stuck with me as a beautiful expression of the cage formed by rhythm-uber alles.) It comes with its own challenges – a beat permits other players to rest easy knowing that there’s another instrument creating the progress or motion in a piece, all they need to do is illustrate over the top of it. But there’s a machine-like monotony to music set to the omnipresent beat – do you not get enough of it day-by-day? Listening to performances in which drums deviate from their traditional status as show-off metronome and become percussive sound generators, free agents, are quite enthralling for a time – if the players are able to incorporate the full range of possibilities present with a physical kit. Thurston seemed to desire a partner in his desire to derail the core instrumental line-up of rock ‘n’ roll both for it’s comforting familiarity as well as the perversity of dragging it onto fresh soil. There’s a similarity also in the instrumental technique of Thurston’s early improvisation to the work of a drummer – famous images from the Eighties of SY scraping or beating guitars come to mind at once. This was still the core of his tactics in the mid-Nineties so there was a dissolute harmony in working alongside an instrument being put to similar forms of percussive misuse.

From there Thurston began offering his guitar to other possible line-ups. In the mid-to-late Nineties the possibilities of electronica were being touted as the ‘next big thing’ with superstar DJs and celebrity remixers all the rage. No one was immune even if the result was very different indeed. 1996’s “Electricity vs. Insects” 7” commences a spell in which electronic effects play a relatively prominent role as a partner on recordings. This was the first real work in this realm since JG Thirwell’s manipulations back in 1987. Phil X. Milstein’s tape work features on a 1997 release (the Cramps referencing “Songs We Taught the Lord Vol.2”), then the Walter Prati-featuring works “The Promise” (1999) and “Opus” (2001) emerge, with “Root” (1998) and the Christian Marclay/Lee Ranaldo performance “Fuck Shit Up” (recorded live in 1999 and released in 2000) fitting into the gaps along with the split 7” releases with Deison (1999.) That means that every year from 1996 to 2001, at least one of Thurston’s three to six releases a year made substantial use of electronic effects – that’s a substantial presence within the discography. It doesn’t last, however. After that year, despite releasing vastly more material, the majority has been with more traditional instrumentalists as opposed to electronic manipulators. The experiment certainly made sense and was embraced with a certain gusto – “Root” was a fairly high profile release at the time with Thurston turning over his creations to a range of alumni for their manipulation. It also makes sense why it wasn’t necessarily a stellar move; ultimately Thurston had already converted his guitar from a traditional combination of sounds into a fairly unlimited sound generator with the entire loop between his hands and the amp output brought into play and with a vast range of physical and electronic effects deployed between those two points to warp the results. With Thurston’s guitar, essentially, already an electronic device creating noise, there was little electronica could bring that he wasn’t already. Similarly, the rhythm-based results of a majority (not all) electronic music of the modern era had little in common with the direction Thurston was taking. Finally, there’s a point regarding the nature of collaboration most satisfying to Thurston. On The Promise and Opus electronics were a third player in a trio, not the second in a duo; the same goes for the performance with Christian Marclay; Thurston wasn’t present in studio with Deison or with the guests on “Root.” Thurston’s discography has grown fat on live collaborations in the context of which far more interplay, exchange, response and counter takes place when the players aren’t hunched over wiring let alone a laptop. 2014 did see Pedro Sousa contribute electronics (as well as saxophone) to the “Live at ZDB” release of an October 2012 performance – likewise the earlier flurry of activity with noise scene artists like Aaron Dilloway (2006) and experimental/industrial stalwarts like Commissar Hjuler (2009-2010) or the New Blockaders (2007) mean electronics have never disappeared entirely from his line-ups. He’s a willing joiner in most situations.

(As a side-bar, it’s very visible that laptop artists are increasingly aware that live performance is both aural and visual – something they, crucially, lack. While a guitar, drums, sax allows a link between the sound being experienced and the motion and emotion of the person performing – a human connection between performer and those present – that link is crippled when the visual is gone. That’s why most laptop artists are confined to dances – where the audience provides the shared experience and physicality – as support to vocalists or other performers who can provide the human face and focus, or by deploying a battery of filmed visuals or on stage performance. The finest laptop artist I’ve witnessed is Leyland Kirby. As V/VM he supported Sonic Youth at a show where I still fondly recall animal masked friends of his tossing lettuce and cheese slices at the crowds, attacking one another dressed as animals and generally clowning as if this was a deranged pantomime (I kissed a pantomime horse in return for which they passed the CD someone had thrown into the space between stage and audience – the horse got it for me.) Over a decade later, as the Caretaker, I watched him take the same approach by first performing karaoke to a soft rock classic then rolling off the stage and through the audience, then setting the laptop going and simply sitting on the stage to watch the video diary along with us. I found it totally engaging, one of the best films I’ve seen accompany any onstage performance given it was blatantly personal and came with a personal message written on screen at the start, as well as absolutely showing how alienating the laptop ‘performer’ is from any recognisable human form of performance as an bringing together of observed and observer.)

To discuss and contrast two forms in which electronics can be witnessed in Thurston’s oeuvre, on December 4, 1996 Thurston shared the stage with Phil X. Milstein who might be better classified as a surrealist with an interest in dreams, sound poetry, experimental collages than a traditional musician. The resulting performance is remarkable for the way that Milstein provides the layer of chattering sounds that would normally be provided by an inattentive and disrespectful audience, it’s curious to contemplate my annoyance if faced with ‘conversational audience participation’ on a lo-fi bootleg versus how intrigued I am by the voices and mutterings Milstein entangles into the performance. Given the ubiquity of spoken word samples on the work of bands like Mogwai or Godspeed You Black Emperor (who received ample comparisons to SY’s work) around the time of this performance, it’s curious how little role such shenanigans have played in Thurston’s work. It emphasises that his interest lies in the world of sound creation and musical collaboration, not in the construction or orchestration of structured recordings, the arrangement of sound files on or over other work – he’s not someone desperate to work as an omnipotent music producer. That’s a commentary on his motivation as an explorer of sound – he’s put together bands, brought together collaborators, but seems to feel no desire to boss or manage them in furtherance of a restricted vision of his own dictatorial conception. Maybe that’s where my only real criticism of this release lies – ultimately Thurston does his own thing as a guitarist, while Milstein is off following his own muse. There’s not really any meeting of minds or sounds taking place – swap Thurston out and stick in Slash playing cod-rock moves of the old school and it’d work just as well; strip out Milstein and drop a record by Negativland and it’d rumble along comfortably. The challenge is perhaps one of format; on vinyl there’s no indication of where/when a gambit by one or t’other musician is a reaction to or compliment to the other’s thought process – you can’t see it. That’s a regular pause with an awful lot of improvisational music – one always wonders what is lost when the entire visual component of watching musicians at work is sliced away. The judgment instead must fall on whether the result is interesting as a sonic experience and it has to be said it is worth a listen, re-listen, flip, repeat. Voices submerge, other instruments crack Thurston’s surges, recorded sound is divebombed with guitar explosions while paused fingers are made to run by strafing fire from Milstein’s own guitar. The only point at which the sound placement (or at least the way the record has been cut) seems particularly precise comes at the close of Side B where the final sample states “…Turns the air conditioning OFF,” at which point the record ends. A neat last touch but a long time to wait to be sure deliberateness played any part here.

“The Promise” (1999) has always been a release I’ve felt ambivalent about but marks a crossing point in which the period of electronics peaks and the saxophone, likewise, becomes prominent. Thurston permits the other instruments to screen his contributions, he relegates himself to the background – ultimately letting Evan Parker lead the ensemble. Mea culpa – I’m not necessarily a lover of the saxophone, this undoubtedly influences my feelings here. Track 6, “Children” is the one that most stands out for me – Evan’s see-sawing constancy, the blanket background provided by Walter Prati’s rumbling thumbed bass, Thurston’s occasional interjections with soft runs of notes – it all combines to a satisfying close on track 7, “All Children” with cut up spoken word gradually buried as initial spikes become molten guitar and electronic slag. It’s the physicality of the playing – being able to hear the hand slides at one point – detectable human motion behind the otherwise unidentifiable wall of sound that at times is permitted to simply continue undisturbed, noise as peace. The final thirty seconds pulse like a stylus hitting the end of a song. Chopping a release like this up into passages does create manageable and digestible chunks, while also making it hard not to feel the artificiality of the format given the sounds and activities on display are so similar across the release. There’s something of the gypsy jazz approach to Thurston’s tightly tweeted up-down stroked notes – of course he ladles on the disharmony, the disconnection between notes even as he pulls fairly conventional hammers and trills. Five minutes in “Is” Thurston’s guitar sounds like bones rolled in a closed fist. It’s a release that feels more worthy of live presence – that one would benefit from watching the interaction between the three individuals to see clearly how they exchange ideas. It’s also rare for Thurston to resort to overt noise on “The Promise”, his noises are restrained, tactfully deployed – the gradually relaxed or released strings swooning behind “Our Future” is a case in point. These subdued murmurings feel like a polite chat between people wanting to negotiate a direction rather than anyone wanting to lead. “Opus” (2001) left me similarly uncertain but again that’s more down to my own limited appetite for saxophones.

(Thurston Moore, Ikue Mori and Okkyung Lee in April 2009)

That’s a difficult of course because the saxophone is probably the most prominent fresh accompaniment Thurston has welcomed completely into the fold. Sure, there was no wave sax on Lydia Lunch’s “In Limbo” but it was an expected part of the full band session in 1982, it’s only on “Barefoot in the Head” recorded six years later that Thurston links up for a sax(x2)/guitar duel. Perhaps it turned him off the instrument, made him nervous – it was his first attempt to enter the free jazz improvisation arena after all – but despite the burgeoning activity in the Nineties it’s not until 1999, over a decade later, that the instrument reappears in Thurston’s discography. While “The Promise”, a collaboration with saxophonist William Parker and multi-instrumentalist Walter Prati, was apparently recorded and realised all in that year there was actually a second recording – the “Hurricane Floyd” live set with Wally Shoup and percussionist Toshi Makihara – that same year though not released until 2000. Both collaborations have sequels – 2001’s “Opus” with Prati adding cello to the mix while Giancarlo Schiaffini introduces a trombone for apparently the only time in Thurston’s catalogue; 2003’s release of “Live at Tonic”, a 2002 performance with Shoup, plus Paul Flaherty on tenor and alto sax and percussion by Chris Corsano. From 1999 onward the sax is a regular instrumental foil to his guitar work; Mats Gustafsson makes his inaugural appearance on a release with Thurston in 2000 and there are sax-featuring releases in 2000, 2001, 2003, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011 and 2013. That’s a big shift but perhaps inevitable when swimming in the jazz field. A discovery on eBay the other night that intrigues me, however, is a 1998 release, “III”, by an outfit called The Grassy Knoll. Thurston apparently contributes guitar to three songs by this full-on jazz outfit – I’d like to know more about it but it still presents a shift in the instrumental sound field against which Thurston matches his guitar, one taking place at the end of the Nineties.

The “Hurricane Floyd” release (2000) came with a top-notch back-story. Recorded on September 16, 1999 at the Old Cambridge Baptist Church, Harvard Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts as the titular hurricane blew itself out overheard somewhere. The track marked “Altar Boy, Church Basement” is of particular interest – it’s essentially an early solo acoustic version of “Turquoise Boy” from the 2006 Sonic Youth album “Rather Ripped.” Seeing how fully formed it was so many years prior to its use in the full band context makes one wonder about the roots and origins of many SY pieces. Here it has a close-micked clarity that is truly enviable – the recording quality across this whole release is of stellar quality. “Retribution of Sorts”, the final piece is gorgeous, a keening midnight saxophone meets Thurston’s steel-drum high notes in something that, for a couple minutes is full sentences before it reverts to conversational point/response or talking over one another. The drumming from Toshi Makihara is actually, in my view, one of the most enjoyable pieces of the release. Throughout he seems comfortable pausing, making his interventions precise and effective, his choices – 13.50 into the track he begins working the cymbals over as a perfect complement to Thurston’s gradually building train-motion and Wally Shoup’s controlled angles. As ever these things at some point have to resolve in a blow-out but the gently walking out end minute is a nice touch. Off to review by starting with the back-end of a record but the acoustic break before resuming does help appreciation of the last piece – even on an improv record the positioning of pieces can make a regal difference. The opening minutes of the first track is effective; the drums keep it together with moves that make me think of someone spinning a drum-stick in their hand but somehow hitting a dozen beats in the same movement. Initially the guitar and sax make exchanges – one instrument then the other with only mild overlaps. Then they slide in beneath one another though pauses seem well-nodded from one to other – 4.45 in or so a switch of vibe and mood. Often where the guitar/sax come closest to merging is in the blue notes of the finales – otherwise skronk and screech can be world’s apart. Track two is more effective in that respect, background rustling – a truly unusual product of the percussionist’s art, cable noise, brevity of breath…Shifty commencement taking a full seven minutes to crash down into volume competition.

The “Live at Tonic” (2003) release caught a four man line-up on the night of September 14, 2002 – again, Wally Shoup was involved, this time with Paul Flaherty and Chris Corsano, a regular duo at the time. The result is two sax deep with Thurston really submerged into a cataclysm of squalling honks, thumps, clatter and hoots. He reacts by creating a base-layer, a series of longer tones and drones that take a while to really notice – it’s like how bassists are always underestimated because the undercoat is never as brilliant as the gloss – but the gloss wouldn’t shine so flawlessly without it. I’m at a crucial disadvantage here in that I must confess to simply not really liking the saxophone as an instrument – how can I truly appreciate a recording that foregrounds an instrument that creates a sound that often curdles my ears in too high a dosage? No, that’s unfair, I simply prefer it when used with more subtlety; 14.45 into the second track (second set) the band, for the first time, quietens down. Thurston curbs metal hums in a wash across the backdrop, each saxophone drops in note runs that can actually be appreciated because they’re not consumed in a rush of sound, the drums dash and scatter across the soundfield – the next few minutes are the first time the instruments have separated, have become distinct voices as opposed to monolith blast. Then the one-upmanship recommences, a gradual rise in volume as one player outdoes the other and ups the ante which, unfortunately, tends to mean doing more, making more sound, when those past three minutes of discretion were far finer demonstrations of skill. That’s where I’d distinguish my bias; I like noise releases that allow my ears to catch a sound and follow it – to be taken a journey even in the most dense thicket of volume – I dislike hyperactivity where there’s no settling long enough to catch or appreciate. I can enjoy the sound of a bus engine throbbing while hating the chattering of an impolite crowd.

The “Flaherty/Nace/Moore” release of was another opportunity to study Thurston in saxophone company. Flaherty’s playing tends toward short yolts and yanked knots of sound, the presence of a second guitarist offering a more steady background. First track “Sex” is short, stubby, anxious…Jeez, feels familiar somehow. The saxophone rubs up against grinding metal for what is essentially an introductory track. The sense of instruments going in opposite directions is palpable; the saxophone rises as the guitar is torn slowly down the gears or vice versa. It’s a nice contest. “Drugs” commences with a gentler ringing of bell tones, a softer tone, before the saxophone once against spurts and whirlwinds over the top – by nine/ten minutes in the piece has disintegrated into strafing runs of guitar tone over a spluttering rhythm with ‘squirrel in fear and pain’ sax. Ugh. By twelve minutes in there’s an angle grider tone set against someone gasping for breath then back to the squeaking. At fifteen minutes the guitar is bobbly, bubbling against the crack of the second guitar – the sax is reduced to cine-tones. It’s a f***ing cacophony. It might seem strange in the context of this discussion to criticise something on that basis – what am I lacking? What’s my complaint? It’s hard to define…It’s the sense of noise to no end – the saxophone essentially. The sax has a conversational tone, a motion based on breathing, that the hand-motion required with a guitar just can’t keep up with. The problem is that there’s so little differentiation in the basic sound of the saxophone once the idea of playing a tune or melody has been abandoned and there’s so much movement in the sound that it’s a deluge of near identical moments with no direction longer than seconds. We’re into the terrain where something is more fun to play than to listen to. But then, just my tastes. I can’t complain.

(Thurston Moore, Joe McPhee and Bill Nace live in 2012)

A truly random excursion was Thurston’s contribution to My Cat is an Alien’s “From the Earth to the Spheres” split CD series (2004.) “American Coffin” consisted of Thurston working with a piano for some 10 minutes before he becomes far more comfortable manipulating the recording equipment. Simple truth is that, like with his guitar work, there’s a knowledge of the instrument at work in order to achieve the result – it isn’t a complete novice at work, his progress along the keyboard is too smooth, his combining of notes too seamless to be random – for the minute from 5.40 he displays a sudden burst of quick fingers that indicate he’s hiding a certain skill. What he seems to be doing is simplifying his performing style to evade the clichés of standard technique. In that respect there’s a definite similarity with his earliest guitar work in that notes are hammered over and over until they become an effective rhythm or mantra – then a switch takes place whether in tempo, rhythm, note while other characteristics are retained. Still, I’d have to say it’s a horrendous listening experience. The background microphone rumble is a neat feature but listening to high pitched piano tones pinging at one’s skull gets pretty unendurable after five minutes let alone ten. Ultimately there isn’t sufficient deviation in the sound – that brief burst around 5.40 of note-runs reoccurs around 8 minutes in with les surprise, every now and again he moves to focus on the low notes creating decaying clouds over which he sparks a few notes but always he reverts back to the jabbing of keys as the base from which he deviates, that stability is somewhat dull. The move into a second piece has a certain interest a drum machine moves in with a shifty rhythm, then a range of samples (perhaps just a radio?) starts to fire off keyboard tones, repetitive dance music, burping beats, all somewhere inside the continuous dulled tone of feedback. It’s a fair point being made, that the acceptance of noise as part of the everyday arsenal of electronic-based music makes a mockery of the resistance to its presence in guitar-based music. There’s a point being made about the death of rock and roll, the ‘American Coffin’ of the title, as the desire to keep repeating the same ‘authentic’ old moves led to an unwillingness to expand the palette or move onto new vistas in mainstream rock. The result was the handing of the baton to hip hop, R n’ B, dance – where a visible appetite existed. A sample – the final four minutes of the piece – were torn from here and inserted into the “Trees Outside the Academy” release. It’s certainly possible to note that the piano is a rare presence in Thurston’s discography in general – in some ways there’s been a settling into a set of standard partnership; drums, sax, guitar, various noisenik activities – line drawn.