More stats and general musings on Nirvana to follow…But wow, things are getting busy. The book is due back from the printers this Friday – fingers crossed! In the meantime…This is an early summary of each chapter – just a set of snapshots rather than a full picture of what is covered in each one. Oh, and yes you’re right, each chapter is named after an album by a band Kurt expressed a liking of (The Minutemen, Scratch Acid, Big Black, etc.) the exception being Songs the Lord Taught Us, but it was too good a title to pass on:

Foreword

Months of total immersion in Nirvana has not always led me in healthy directions…You have been warned… J

1.0 The Greatest Gift

Incesticide sold more albums than any punk album in American history…Yet its qualities and pleasures have been roundly ignored. I set out the case for the album’s status in terms of the quality of what it contained, the care the band took over its creation, its artwork, its liner notes, its songs

2.0 (MIA) The Complete Anthology

Biographies of the band have stated that Nirvana’s first label Sub Pop teamed up with DGC to combine efforts and create Incesticide…They’re wrong

Fresh interviews with the key individuals at Sub Pop indicate that there never was a planned Sub Pop release. Incesticide was dreamt up and planned entirely at DGC and by Nirvana

3.0 Two Nuns and a Pack Mule

Even Incesticide’s back cover was a comedic image and with the selected cover songs, plus Sliver, on the album its always been the most fun of Nirvana’s albums

Yet Nirvana’s brand of humour was often caustic, aggressive and used as a form of attack — the band were at their funniest when taking sarcastic swipes at the scenes, bands and individuals they despised which can be seen in lyrics, in behaviour on stage and their approach to media and TV

4.0 The Rich Man’s Eight Track Tape

The chapter indicates the deep thought that Kurt Cobain put into structuring and sequencing the songs on the album — there’s a joke running through the entire album and likewise an attempt to mimic Nevermind, making this album its mirror

It’s now possible to see how many songs were refused for this album and to reconstruct the logical decisions that were being made in terms of what was included and why these fifteen songs were chosen

5.0 My War

Nirvana are portrayed as an apolitical band yet they were permanently committed to anti-sexism, anti-racism, anti-homophobia throughout their career which has been ignored because Nirvana’s approach was to have the conversation with their fans rather than to focus on ‘big banner’ causes aimed at attracting media comment

The liner notes within Incesticide are exceptional — a rock star deliberately driving away his audience by telling them to “leave us the fuck alone!” and doing so on the basis of their views on gender, sexuality and race

6.0 Double Nickels on the Dime

Nirvana were not an inevitability, despite the subsequent focus on jokes about ‘destiny’ and how they were going to be rock stars

Nirvana as a phenomenon occurred as a half dozen identifiable factors came together. Incesticide was part of the band’s attempt to resist and sabotage fame

7.0 Project Mersh

The literature simultaneously portraits Kurt Cobain as anti-commercial on a gut level and ruthlessly ambitious and commercial in his actions. I feel this schizophrenic portrayal arises from a misunderstanding of what music meant to him

In this chapter I focus on the desire for control and freedom as the driving motivations; whether an action was commercial/non-commercial simply wasn’t something that Kurt Cobain was primarily interested in hence the consequences of his actions could be either without it representing a ‘fracture’ within his personality

8.0 Post-Mersh

Incesticide showed Nirvana trying on different styles as they learned and evolved with a far more underground sound, with the sound of Kurt Cobain’s first recordings entirely abandoned then resurrected for Bleach

Alongside the album Kurt Cobain attempted numerous experiments with his vocals, with recording techniques and with guitar that ended as he headed mainstream

Incesticide represented the span of Nirvana’s experiments…But not necessarily of Kurt Cobain’s experimental urges

9.0 Hairway to Steven

Nirvana’s evolution can be followed by examining how they switched from covering metal songs to alternative rock tunes to more mainstream fare — Incesticide was their key statement not of the bands that did influence them but of those they wished to be seen to be influenced by, the album serving a ‘propaganda’ purpose that downgraded their rock roots in favour of emphasising their punk favourites

10.0 Big Black Songs About…

Like any writer Kurt Cobain had a personal style, one that evolved between the songs seen on Incesticide that originated in 1987 and those he became famous for. I suggest that he had three key song modes

Kurt Cobain wrote quite a number of ‘story’ songs between 1987-1990 then abandoned linear narrative altogether, similarly the character sketch was a regular trope of that period which he soon abandoned in favour of direct personal addresses announcing his mind-set and situation via song

11.0 Over the Edge

Having shown the forms in which Kurt Cobain created lyrics, we look here at exactly when his writing underwent changes and what may have events drove those changes

12.0 Family Man

As well as his writing style Kurt Cobain dwelt on specific themes and ideas that either evolved or remained constant all the way back to his first recordings in 1985 — the focus was regularly on issues arising from family, gender, sexuality

This chapter proposes a unifying concept that draws together material from as far back as 1985 and as late as 1993 — I posit that Kurt Cobain was the most psychologically motivated rock star the mainstream had ever seen

13.0 Songs the Lord Taught Us

A song by song dissection of the fifteen tracks on Incesticide seen in the light of the lyrical themes, musical patterns and Nirvana background described in this volume

The chapter synthesises the themes and ideas that have been expressed throughout this work and applies them to each of Incesticide’s tracks here ordered by the dates on which they were recorded/released keeping the songs in their chronological context and alongside their immediate ‘family’

14.0 Dry as a Bone

By 1992 Kurt Cobain was barely writing songs, yet there are still rumours of unreleased material. The paucity of truth in such rumours, the absence of truly impressive outtakes shows Incesticide was actually the cream of Nirvana’s leftovers

This entire work has been made possible by the depth of work done by bootleggers and unofficial releases over the past twenty years creating a situation in which the band and the record label have been supplanted in terms of knowledge

15.0 Coda

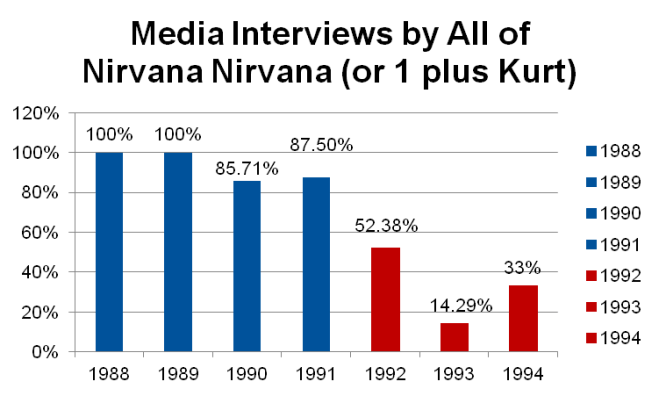

From 1992-1994, Nirvana barely existed as an actively creative unit. This chapter makes the case for seeing those years as the story of a band that was barely alive

Kurt Cobain’s suicide note was the third of just three written statements made to his public 1991-1994; the first was the Incesticide liner notes, the second his contribution to The Raincoats’ album release. What stands out is that the suicide note was a deliberate concealment, an attempt to avoid having to explain himself or his reasons

Reading Nirvana: A Bibliographical Note

In the case of Nirvana, fan-led initiatives online are actually the best source of raw data — whether on live shows, songs, sessions, past interviews and media reports — so this chapter begins with a brief tribute to LiveNirvana, the Nirvana Live Guide and the Internet Nirvana Fan Club

The chapter then summarises the various strands of the bibliography; biographies, cultural-historical studies of grunge as a phenomenon, song/album studies, then onward into photo books and other more unusual items covering English language publications on Nirvana through to October 2012