The history of popular music has not been written by musicologists, it has been written by English literature students. This has, on the one hand, gifted the world beautifully descriptive and emotive articles and musings on music — but it also means that reading about music is essentially a biographical and story-led experience, not one involving a deep knowledge or understanding of the mechanics and structures underlying the subject. It’s a bit like learning your history from Hollywood or your politics from the tabloid press; articulate and/or combustible commentary trumps detailed and learned knowledge.

Among the negative consequences is that most writing on music is written in the mode of literature. By this I mean that discussions of music are given a linear progression, a plot, in the same way that fiction would be. While this results in a smoother reading experience, what I take issue with is the idea of an artist ‘evolving’. Each musician is given an origin (setting the scene for the story about to ensue), then early flowerings (the discovery of the plot or dramatic scenario), next a triumphant realisation of their ambitions (the plot revealed awaiting resolution), followed by a development toward new desires (the wrapping up of the plot and tidying away of loose ends.) This linear evolution implies an accreting process with a forward momentum in which elements are built on top of one another to create something that is a descendent of what came before; it suggests something ‘more’ and potentially better in some sense.

I feel that the idea of evolution is a poor one through which to understand musicians. Creative musicians are not engaged in such a linear journey; they are not piling brick on brick to create a single unified product. Nor are they pressing toward a solution in which a musical choice can be seen as the logical end-point; there’s no such tidy resolution of creativity. Instead individuals motivated to create choose between different ways of satisfying the same base urge to express; the means used are incidental to the unvarying nature of the desire at work and therefore it’s the equivalent of, when writing, using a pen one day, a pencil the next, joined up hand writing one day, capitals the next, a laptop here, a text function on the phone there — it’s not a single journey toward “better writing”, it’s a range of options deployed as appropriate and by whim.

Those initial impulses guiding an individual to create are immutable even if what they wish to express does change; instead of a person on a journey imagine instead a person sat unmoving as different tools are placed around them in a circle — the individual selects a tool but the individual remains unchanged even if the modes of expression alter. By that same token, instead of seeing, for example, the switch from one sound or style of music to another, or from one grouping of collaborators to another, as a case of improving upon a prior approach or reaching some kind of higher level or more greatly desired condition — simply see them for what they are; an arbitrary choice, a hand outstretched to some new way of fulfilling a static drive. It relegates questions of better/worse to the realm of individual taste where they belong.

In the case of Nirvana, did Cobain’s music truly evolve between 1986 and 1994? I’m not saying that it did not change; I’m a great believer in Kurt’s impressive ability to adopt new models from within the punk milieu in which he was ‘birthed’ — what I’m suggesting is that the fact it changed did not necessarily mean it improved, advanced, moved forward. Erase the positivist conceptions and simply see change; an arbitrary process in which motion alters what was there before but does not necessarily create a more beneficial, desirable or higher state. The band Devo chose their name to acknowledge one variant of this line of thought; Devo were named for the concept of Devolution, that something can evolve into a less complex, less advanced entity.

As an early example, a long while back now there was scepticism that Spank Thru had indeed been a song on Kurt Cobain’s 1986 Fecal Matter demo. The song was believed to be too advanced for a young and inexperienced musician to have written and therefore it led to doubts whether it could ever have featured at so early a stage. This view has been proven incorrect. What was getting in the way was that people were acting on a gut belief in progress; despite having no evidence they instinctively felt Kurt Cobain must have become ‘better’ over time so he couldn’t possibly have emerged early on with relatively honed writing skills. In truth, and firstly, Kurt’s ‘learning’ is unavailable to us — Fecal Matter is the first available recording but the failings of the archive, the inability to see practices earlier than 1986, led many to position Fecal Matter as the ‘learning’ when in actual fact it was the end product resulting from a lengthier teenage striving to express musically.

As a second crucial falsehood, the kneejerk reaction was to believe that Fecal Matter could only be understood in relation to future music — that the record was incomplete in and of itself and so only had (and has) importance as a signpost on a journey to a supposedly superior future product. Instead, it’s better to think of Kurt Cobain creating precisely the music he was capable of and that suited the urge of the moment; what he wanted to write was relatively aggressive slowed down hardcore, grunge in essence, with lyrical snipes at the world around him. Instead of the shift to more new wave-orientated music and obscurist lyrics in 1987-1988, as seen on Side B of Incesticide, being an improvement, it was merely an alternative. This fact can be seen in the way that Nirvana’s sound in 1988 failed to develop further along that route and instead devolved back toward a sound on the Bleach LP of 1989 that was far closer to Fecal Matter than to the songs created in the gap in between (Polly, Beeswax, Mexican Seafood, etc.)

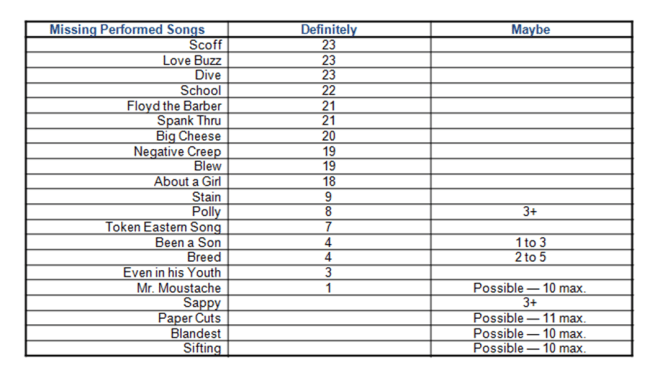

A similar unwillingness to see each creation in isolation and without the mental structure of ‘steps’ and progression has also damaged the reputation of Bleach. Kurt’s own words, that it was basically a grunge-by-numbers album, are used to legitimise the idea that it was a failed experiment when, in actual fact, it served Kurt’s then desires — to be recorded and have a music career of some form — perfectly acceptably. Commentators tend to highlight and praise two songs specifically because they were linear forbearers of future music; Love Buzz and About a Girl. This means ignoring the fact that Blew was the song from Bleach that appeared at the most concerts and persisted from 1988 until 1994.

Much nonsense is written about how About a Girl foreshadowed a Beatlesesque dimension, the pop aspect to Nirvana’s sound. I’d argue that About a Girl — written after Polly, after Don’t Want it All and Creation and the early version of Sappy — let the way to only two more songs with an acoustic vibe, Dumb (an extrapolation from Polly) and the minimalistic Something in the Way. By that reckoning there was far more to come from the pop punk vibe of Bleach than from the one-off About a Girl. Love Buzz does have a greater claim, it has the loud-soft Nirvana would eventually settle on briefly but again, claiming a direct connection from Love Buzz to Smells Like Teen Spirit et al. means skipping the musical explorations that took place in 1989-1990 in which songs continued to roar from beginning to end (Dive, early In Bloom, Breed, Stay Away) or in one or two cases started quiet then got louder (Sliver primarily plus the cover approaches to D7 and to Here She Comes Now.)

The entire intermediate period after Bleach, gathered up on Side A of Incesticide and on the Nevermind Deluxe Edition primarily, is written of as if there was a step-by-step motion connecting Bleach and Nevermind, as if a full two and a half years were simply a ‘warm up’ and practice session with Nevermind as an inevitable outcome; a force of nature that was bound to sweep though Nirvana’s music. This ignores Nirvana’s garage pop dalliances, doesn’t admit that there might have been any alternatives to the band being swept up on DGC and pumping out a commercial punk rock/pop rock album. This doesn’t permit Nevermind’s predominant styling to receive the credit it deserves as a relatively recent experiment for Nirvana.

Talk of evolution halts after Nevermind, instead the chosen narrative is the fall of the hero — In Utero is viewed only as a reaction to and consequence of Nevermind’s success, in plot terms it’s a fairly traditional ‘pride before a fall’, hubristic storyline in which someone is destroyed by their greatest achievement. Again, this coating of inevitability glosses over the extent to which a lot of In Utero had already been written and therefore was coterminous with, rather than a development from Nevermind. Similarly it doesn’t give Kurt Cobain a choice in his fate, nor does it give sufficient emphasis to the longer term reasons for his lack of desire for life. In Utero, in terms of the song forms on display, doesn’t fit any kind of evolution; the addition of more naturalistic recording techniques and rougher sound may be a change but it isn’t a progression or a development — it’s an alternative.

My point would simply be that the music of Nirvana deserves to be viewed more in terms of its overall coherence and unities, disunites and differences rather than as a set of distinct stages pasted over the top of events and tombstoned with an album in a way that doesn’t ever speak for the full range of songs that are meant to ‘fit’ in each component of that narrative. Kurt Cobain used a variety of styles — punk, grunge, hard rock, new wave, alt. rock, garage pop, electric blues, whatever you want to call them — depending on his collaborators at that point in time, or his instincts, or the technology and/or business surroundings acting upon him. A graph showing a simple rise then slight decline would be fine if discussing his commercial prospects but fits poorly to his musical activities.