I finally, at long last, finished reading the “Whatever Happened to the Alternative Nation?” articles yesterday:

http://www.avclub.com/articles/part-2-1991-whats-so-civil-about-war-anyway,46507/

In one piece, the very reasonable comparison is made between Axl Rose and Kurt Cobain. The obvious comparisons – small town misfits, serious parental issues, physical similarities which is why they could both fit the required rock star mould of 1991-1992 – are made but the most crucial one is the yearning of each individual for control over their own creativity, a desire to be free of the constraints either of poverty or of management, fans, press and so forth. The crucial realisation, of course, is that a human personality is such a complex accretion of memories, moments and impulses that despite the similarities between the two individuals, an identical outcome couldn’t be guaranteed.

In the case of Axl Rose, aggression was always launched outward; violence toward girlfriends, trash-talking in the media, pointed and explicit lyrical tirades, a refusal to ever take public responsibility for anything that has ever been less than ideal at any point in a twenty-five year musical career. In the case of Kurt Cobain, the aggressive impulses within him were, near constantly, aimed inward; he would commence criticising his own music in public almost as soon as it arrived in the hands of the public, his lyrics dripped in disdain for his various supposed failings, he talked about himself in a persistently downbeat manner in interviews and in private with the hangdog style drawing understandable sympathy. Yet Kurt’s own record wasn’t devoid of violence or threats thereof; he readily admitted to the voicemails left for the two authors attempting to write a book on Nirvana in 1992; he cheerfully made threats related to the Vanity Fair article; domestic disputes did lead to police call-outs… Neither artist was devoid of minor sins; Axl was far more persistently hubristic about it all – Kurt was a sweeter creature when he wished.

Yet there are similarities in their reaction to audiences and the other demands of fame. Axl Rose’s crimes against courteous concert-hosting are well-known ranging from provoking a riot at the St Louis show, to more recently slow-clapping a fan out of the venue, to massive delays in shows, walk-offs and so forth – if it wasn’t Axl Rose involved some would consider it reasonable to walk off stage if things were thrown at a band. Kurt Cobain, on the other hand, had his own sins such as significant numbers of cancelled shows, responding to on-stage provocations by walking off (or in the case of one show peeing into a shoe that was thrown at him), more positively (in some ways) perceived acts of sexism by audience members were responded to with Nirvana halting shows and having a go at audience members. In each case, the band took it as their role to police the audience and react to what they didn’t like.

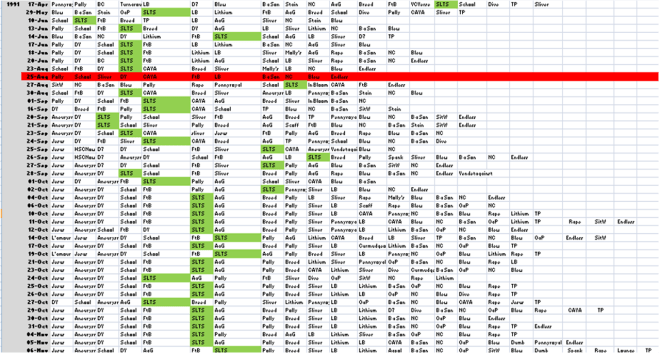

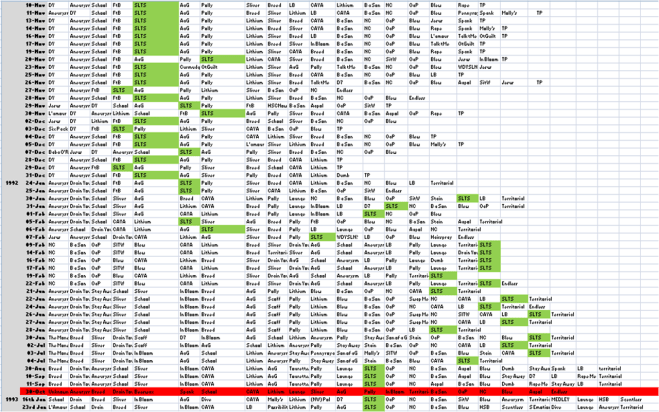

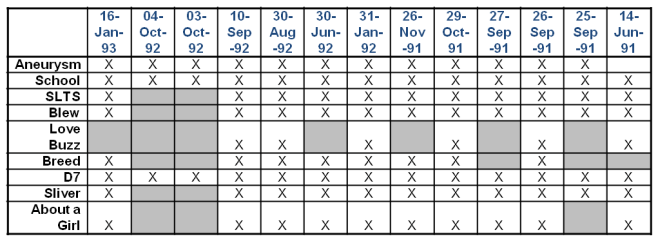

Yet Axl Rose represents something else within the Nirvana story; the way out. Axl Rose’s willingness to ignore the wishes, hopes and desires of all other individuals made him supremely able when it came to building a life outside of the spotlight. His sobriety, compared to the persistent drunkenness or drug issues of his band members, made him the only able to play dictator. Kurt, by contrast, was dictator of Nirvana yet increasingly was unable to steer the ship. Both men increasingly rejected contact with the press if they couldn’t control the nature of the dialogue, similarly time in the studio became a scarce commodity for each band; Kurt barely showed up for band sessions after Nevermind, Axl meanwhile did much of his work for Use Your Illusion separate to the band, then didn’t even appear in studio alongside them for the recording of The Spaghetti Incident? album. A significant area of contrast, at first glance, would be the difference between Nirvana’s relative retreat from live performance versus Guns n’ Roses embarking on mammoth world touring throughout 1992-1993. Yet looking a little further back, Guns n’ Roses gave only 21 concerts in 1989-1990, a wonderfully comparable situation to the 21 shows Nirvana managed between March 1992 until October 1993.

While Kurt Cobain’s control over his environment increasingly fell apart, Axl’s increased as he purchased the Guns n’ Roses brand, shed recalcitrant band members, dispensed with managers and girlfriends until eventually all that was left was Axl and his loyalists. Kurt went through a similar distancing from his former comrades, yet his retreat was toward the companionship of his wife and child on the one hand, and drug buddies on the other. The contrast between the chaos around Kurt and the increasing stillness around Axl is noteable. Axl’s decision was one Kurt Cobain would have envied. Axl never stopped his creative endeavours, this was a man who taught himself rhythm guitar in the early nineties purely to allow himself to more fully realise his own visions and to dictate directions to his band, yet one who simultaneously was willing and able to hook in a large number of collaborators to be spliced into the ever more gargantuan constructions he was trying to fashion. Axl simply stopped participating in the business of music; no press, no live performance, “no” to whatever management ever asked of him (including one alleged incident when apparently, having been pressured to finish some recordings, Axl drove an SUV over the CDs sent to him by his manager) – he refused to be made to treat his music as just a job, or to kowtow to any expectations.

It relied on a very visible rudeness and an unwillingness to please anyone except himself, it needed him to be free of any need to earn money – which was something Guns n’ Roses’ success had already earned him – but Axl Rose did make the great escape. It led to him being criticised rather than praised given he wasn’t playing the game, the music industry machine had been cheated of one of its biggest stars, but Axl Rose survived and made music the way he wanted to regardless of external pressures and now tours, pretty well, as and when he wants. Kurt Cobain rejected the performing, recording and talking aspects of his role, was towed back into it for the In Utero tour and once again ran from it. Yet he didn’t have the same cocoon ready to receive him; and his music hadn’t yet opened up to significant quantities of collaboration; the expression of his visions rested firmly in his own hands and he wasn’t used to letting others craft the sounds around his words or vice versa. He was early in a journey it took Axl Rose from 1987 until 1995 to execute; Kurt Cobain was barely two and a half years into his flight from the music industry.

That’s often how I look at the aged Axl Rose, not as a has-been or a man out of touch with the music world and begging to be let in. Axl Rose shows no interest in whether his record company makes money, there’s not been much mellowing in his refusenik attitude to the media, he still comes out to play as and when he darn well feels he’ll perform his best – it’s very easy to dislike his way of doing things but I think he’s a man who rose to the peak of the industry with all its necessary compromises and pressures, then found the strength and stubbornness to walk away. Kurt Cobain would have loved to take that same walk but had a conflicted desire to be decent to people and to fulfil his responsibilities that meant he couldn’t leave but nor could he stay.

Anyways, here’s Axl Rose on Jimmy Kimmel. Funny, and I want a Halloween tree: